Clarence Peter Helck was born on June 17, 1893, in New York City to Clara Brandt Helck and John Helck.

I am sure I wanted to be an artist from the beginning. This prime urge was intensified during school days when I had encouragement from drawing teachers while accumulating less than passing grades in most of the other subjects. I got by in chemistry only because my full-color sketches of our laboratory experiments intrigued the department head. He was a weekend painter, having his own studio not far from the school.

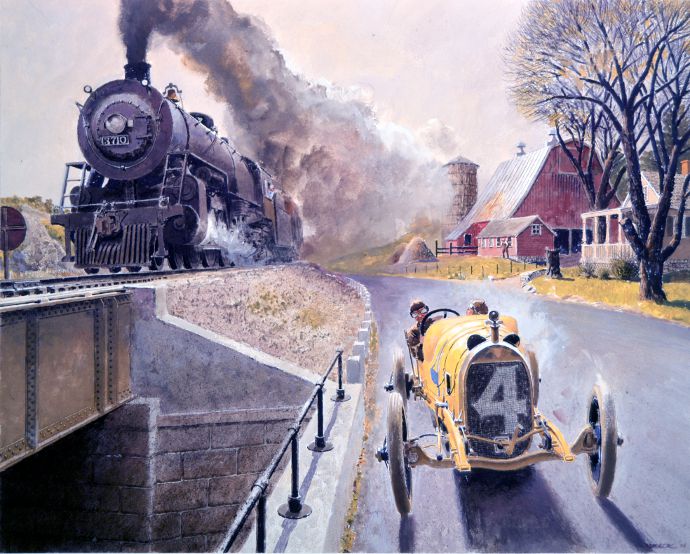

Even before 1900 I was drawing locomotives and trains. Inspirations were close at hand in New York City at that time. The New York Central's double track along the Hudson River was active with both freight and passenger service. Thrills were close at hand with the twice-daily run of the commuting express, The Dolly Vardon, pulled by a sprightly little 4-4-0. Steam, of course. Then east of Central Park was the Central's four-track system. Emerging in glorious roar amid steam and smoke from its Park Avenue tunnel were several hundred trains daily. Even New York's celebrated elevated railways were powered by steam. Over this complex project three thousand trains hauled six hundred thousand passengers every day. Small boys in New York, with or without talents in drawing, were happily aware of all this smoke-belching activity.

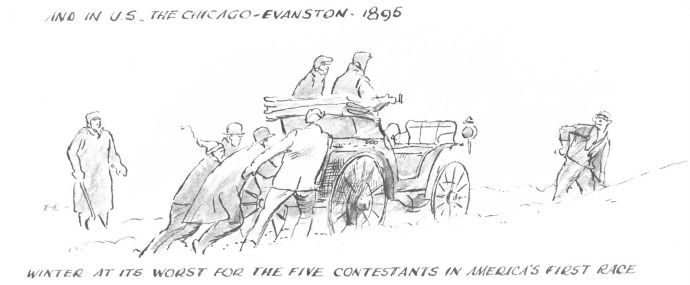

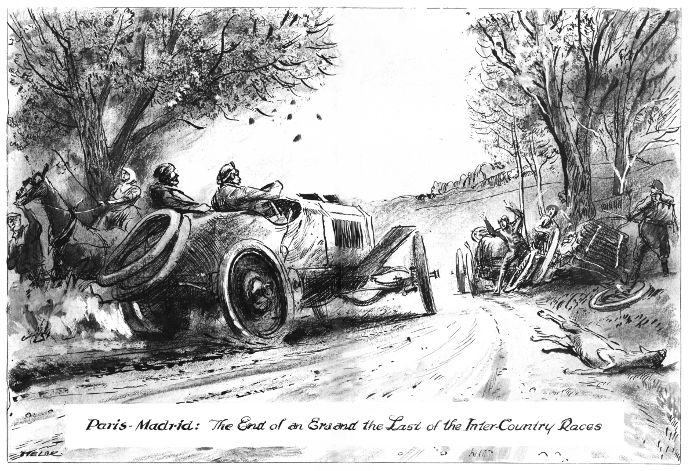

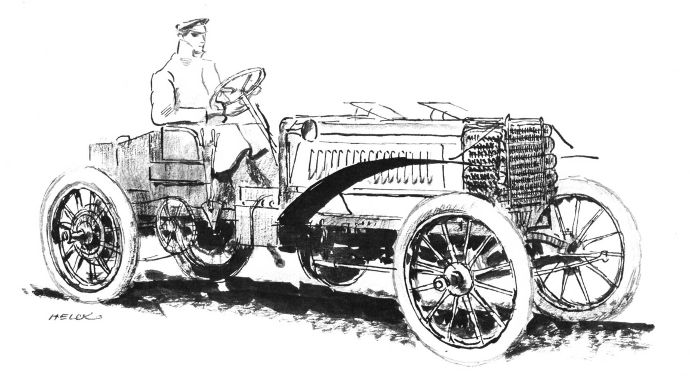

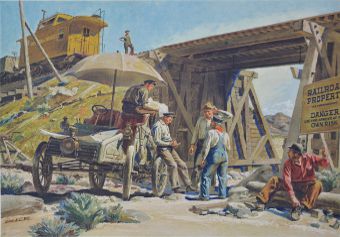

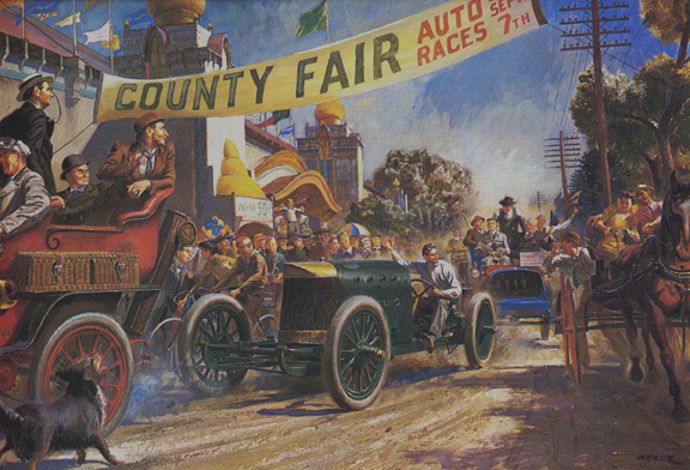

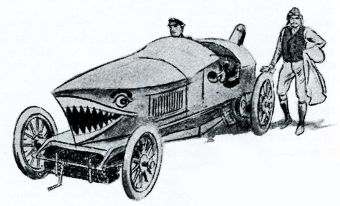

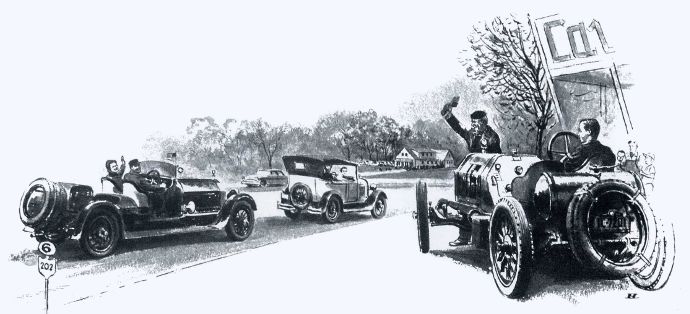

Then came the Automobile. In 1903 1903one of these contraptions parked at any curb was immediately surrounded by the inquisitive of all ages. If left unattended, the juveniles kicked the tires, explored the controls, honked the bulb horn and then scattered swiftly upon the return of the owner or chauffeur. All cars in motion were greeted by young voices bawling "Get a horse!"

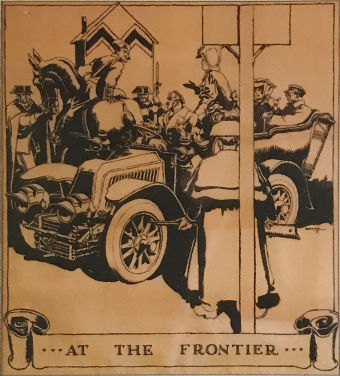

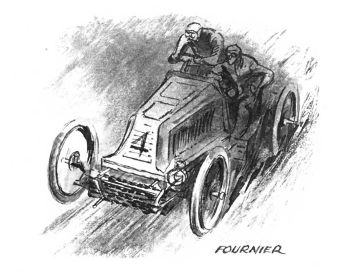

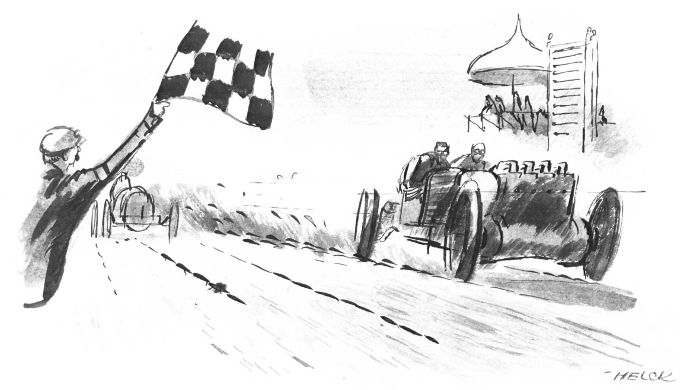

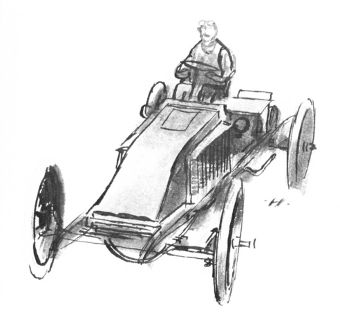

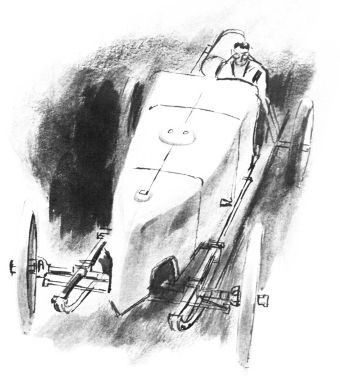

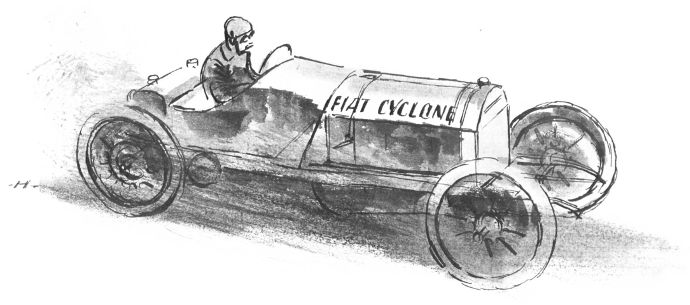

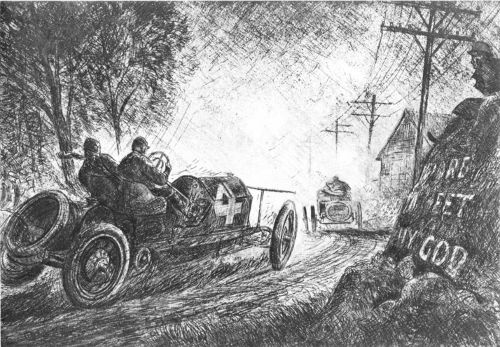

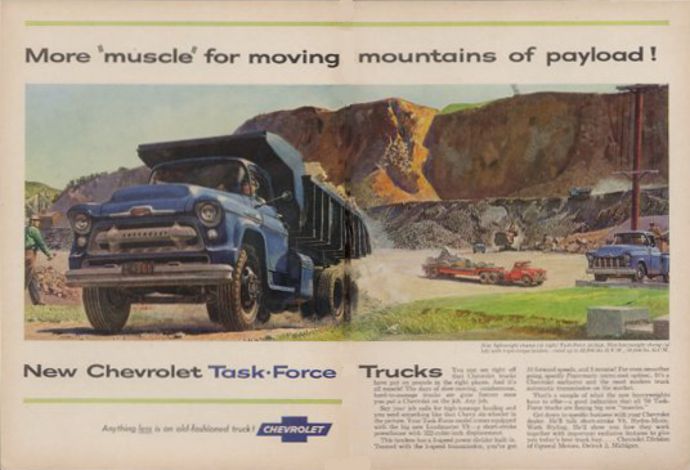

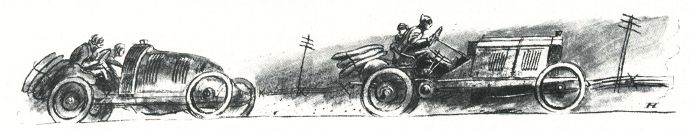

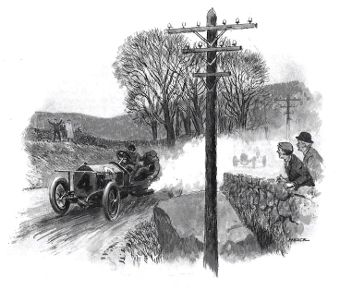

An early Helck, drawn at age 13.

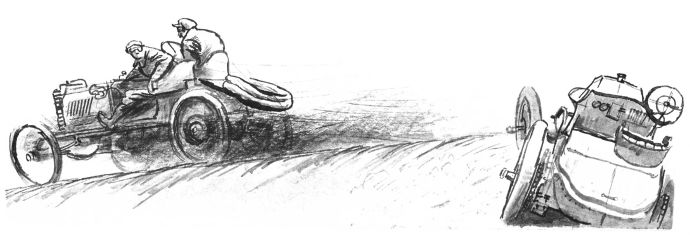

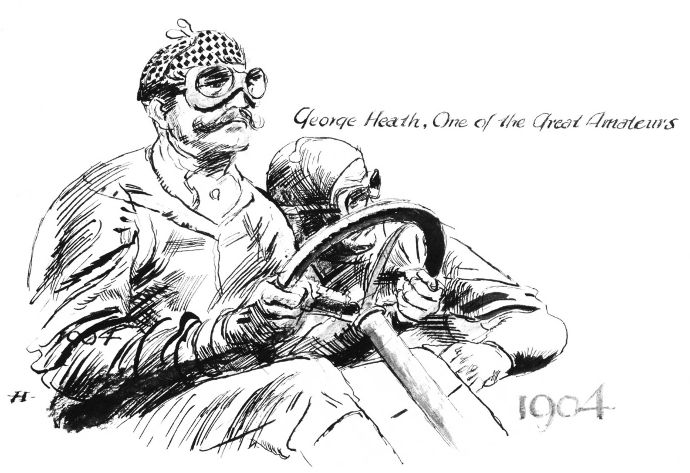

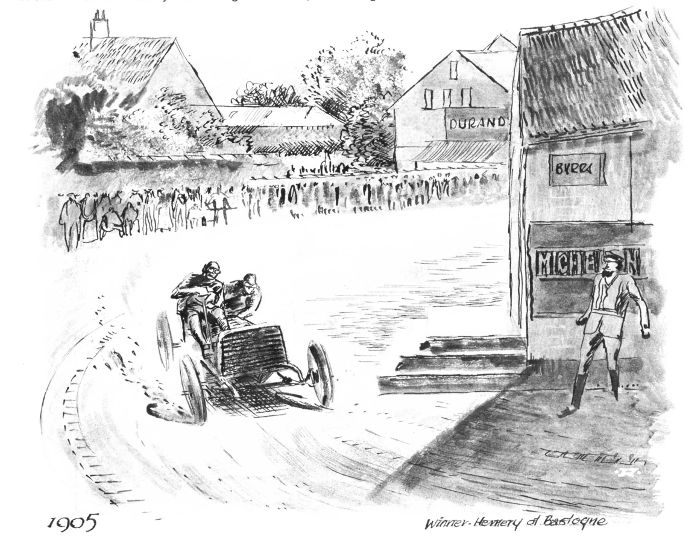

An early Helck, drawn at age 13.By that time my drawings still favored steam engines, but autos were cutting in seriously. However it was in 1905 1905when a kind providence supplied the makings of a true auto addict, with consequent passion for depicting this specie. A well-to-do cousin (whose father owned a Rambler) visited us. At his departure he presented me with copies of Motor Age and The Automobile that carried the illustrated reports of the recent Gordon Bennett Race in France. Then shortly after came the day when an exhaust-barking Simplex stripped chassis pulled to the curb on our street. Its driver gave a warning glance at the swarm of small boys converging on the scene, and then entered the doorway of number 118. On his subsequent return and being assured that the swarm had respected his dissuasive glance-even to abstaining from testing the bulb horn-the driver sensed the appeal in the eyes of the onlookers. Arthur Gilhooly and I were invited to share the front seat (sturdy soap box) and two companions permitted to cling to the rear gas tank attachments. Followed a thundering get-away and a test run through Central Park and up the steep grade of upper Lexington Avenue.

The young driver proved to be Al Poole, already known to me by reputation. He had been riding mechanic for popular Joe Tracy in the 1904 and 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Races, would ride again with "Daredevil Joe" in 1906 and later, as driver, became the record holder (with Cy Patschke co-driving) in 24-hour racing.

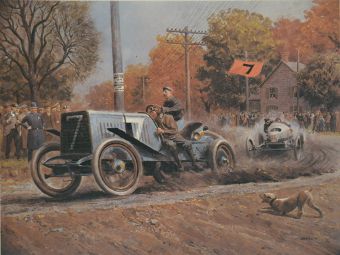

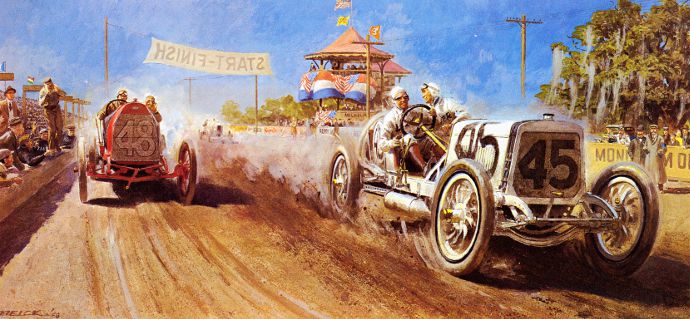

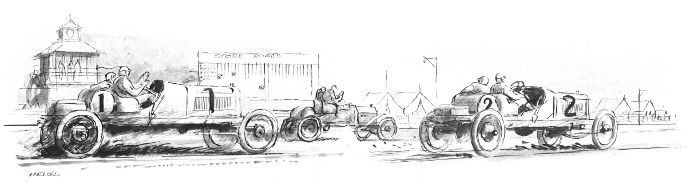

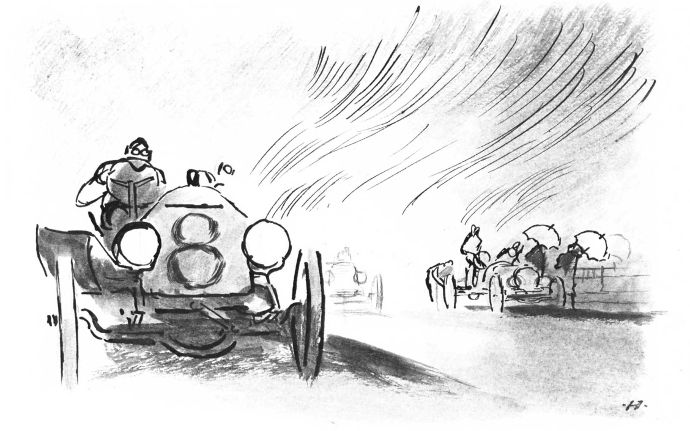

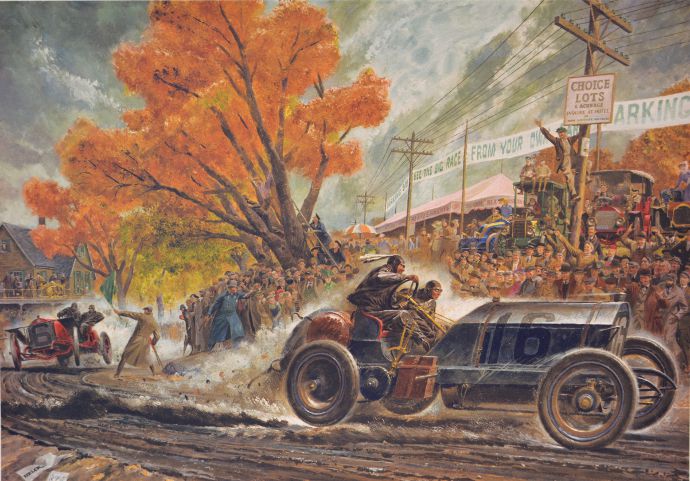

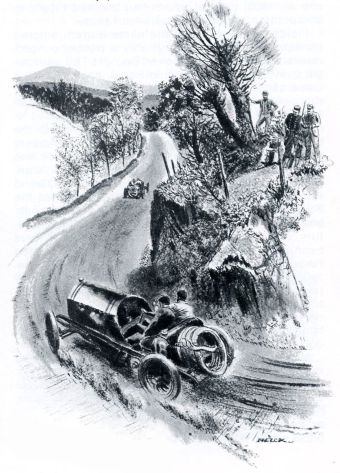

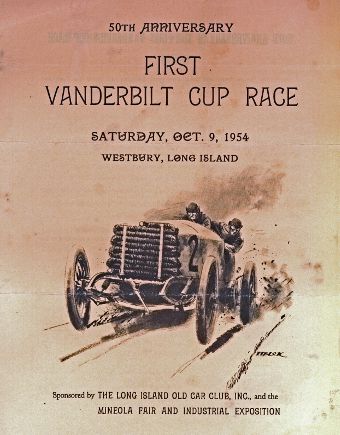

This little spin on the naked Simplex, those that followed, the gift from my cousin stimulated my interest in portraying cars, fast and noisy ones preferably. I contrived ways of including such in my drawings for the school's monthly magazine and its yearbook, on both of which I was art editor. Another factor in shaping future art objectives was the 1906 1906Vanderbilt Race. Here I saw my new-found friend Poole crouched beside driver Tracy in booming flight down the oil-soaked North Hempstead Turnpike. Who could have guessed that the 13-year old witnessing his first auto race would many years later own this very car, the Bridgeport-built Locomobile widely known now as "Old 16".

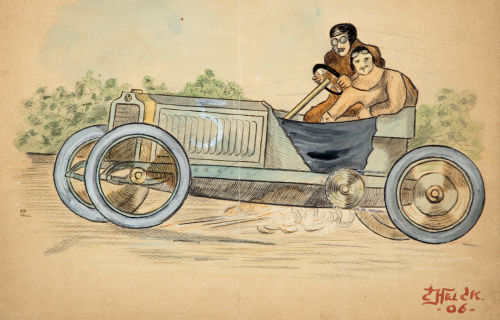

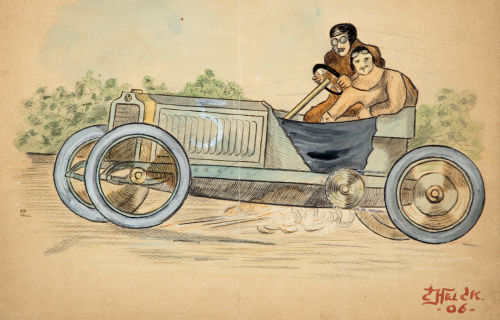

Exide Battery, circa 1917.

Exide Battery, circa 1917.

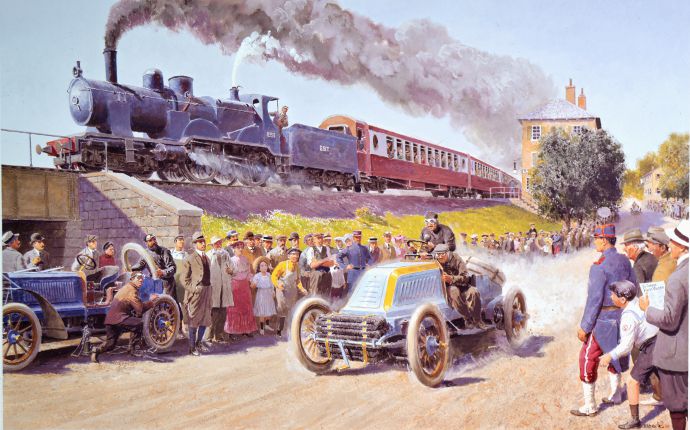

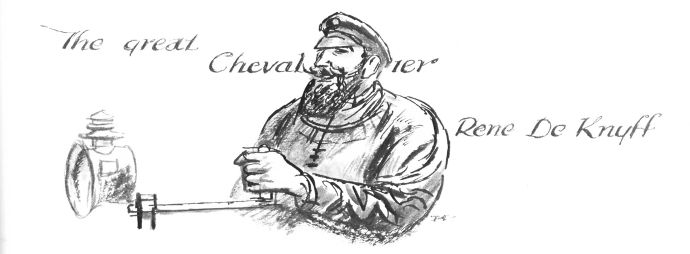

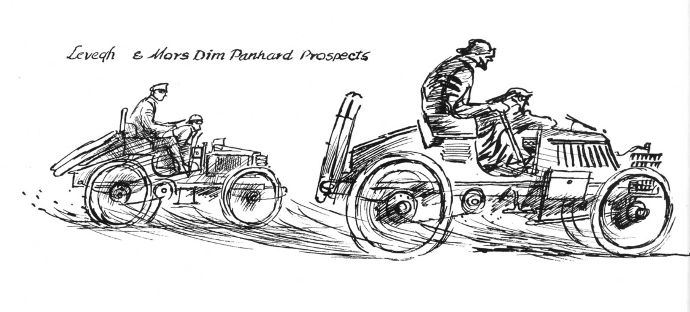

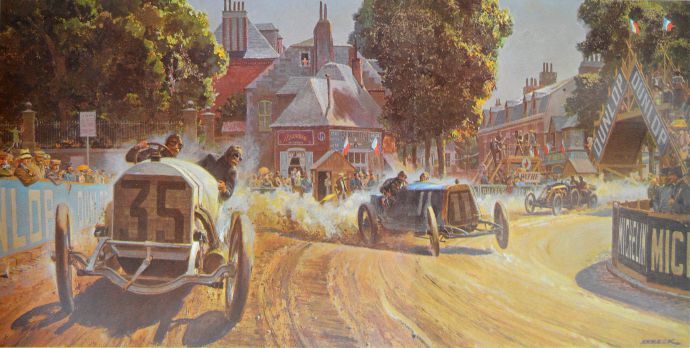

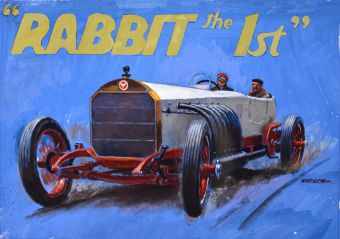

I had also been inspired by the display of spirited racing prints by French artist E. Montaut in Brentano's window. I thrilled to the distortions that added so much to the aspect of speed and to the color that hinted at the grandeur of European racing. I was no less interested in the work of a handful of American artists

Ernest Montaut (1878 - 1909),

Edward Penfield (1866 - 1925),

Walter Appleton Clark (1876 - 1906),

Louis Delton Fancher (1884 - 1944),

Robert John Wildhack (1881 - 1940),

Adolph Treidler (1886 - 1981),

Adrian Gil-Spear (1885 - 1965)

who found the automobile an irresistable subject. Edward Penfield, famous poster designer, emerged from his long obsession with fashionable horse-drawn vehicles and produced equally stylish motoring covers for Collier's Weekly. Another Collier's headliner, Walter Appleton Clark, chose such drama-laden subjects as the Gordon Bennett and Vanderbilt Races. Indeed, Pierce-Arrow advertising in the 1908-1912 period employed the talents of a remarkable group of poster artists: Wildhack, Treidler, Fancher, Penfield, Gil Spear, others. These ads were a powerful influence. They still look good to me today.

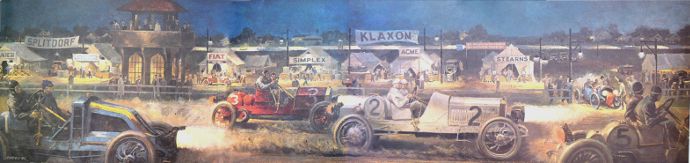

During summer vacation, 19111911, I had my first formal art instruction at the Arts Students League on West 57th Street, a mere 70 yards from Broadway's "Auto Row". Nearest of the salesrooms was Fiat's, hung with Montaut posters, and where on occasion I glimpsed the great Ralph DePalma and the lesser great Ed Parker. Around the corner was the U.S. Tire Building where observing eyes focused on others of the Row's distinguished personages: Joe Tracy, Alfred Reeves, Fred Wagner, Fred Moscovics, Ed Korbel. North and south were the expansive showrooms of the finest domestic and imported cars. In front of them at the curb were their "demonstrators" which included Peerless, Packard, Lozier, Palmer-Singer, Simplex, Stearns and, personally more appealing, Renault, Panhard, Mercedes and other exotic foreigners. Art study in this environment left its mark.

Came an unexpected job 1911 - 1915on the art staff of New York's largest department store, so I left high school, not unhappily, in my third year. From Autumn 1911 to Summer 1915 (a long stretch in the eyes of youth but a mere split-second from present perspective) I had art staff jobs with eight firms. This seeming transience was due to, 1, better offers elsewhere; 2, seasonal layoffs; 3, my refusal to punch a time clock and, are the case if smaller department stores, declining to sell gents' neckwear during the Christmas rush. Two jobs were with movie produclng companies, Lubin in Philadelphia and World Films in New York, where I produced posters which, it was hoped by my employer's "would elevate poster standards" in that tumultuous entertainment fleld. That I was fired by World's Louis Selznick after two weeks suggests that the standards had not been elevated.

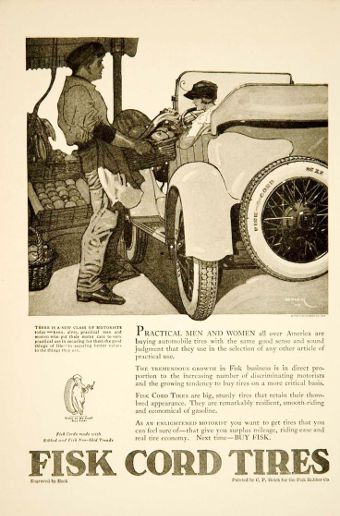

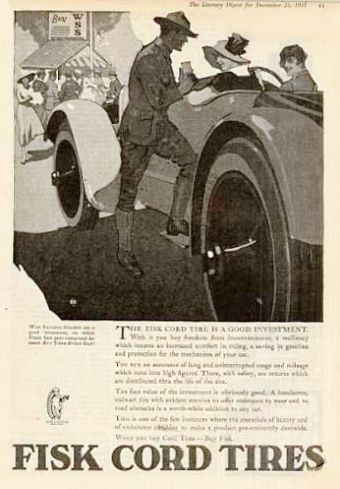

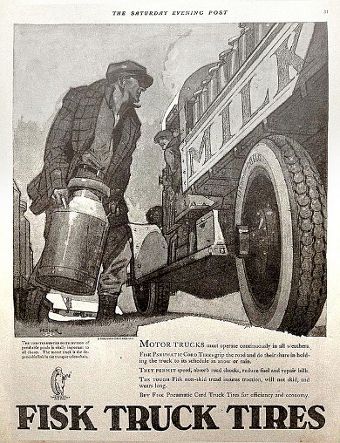

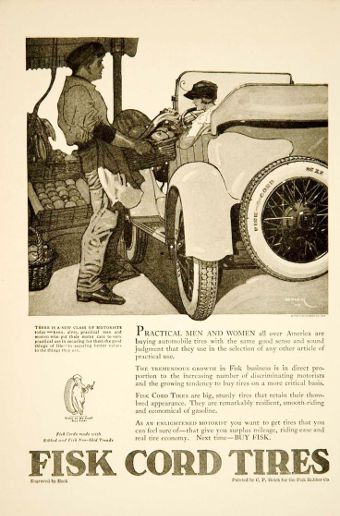

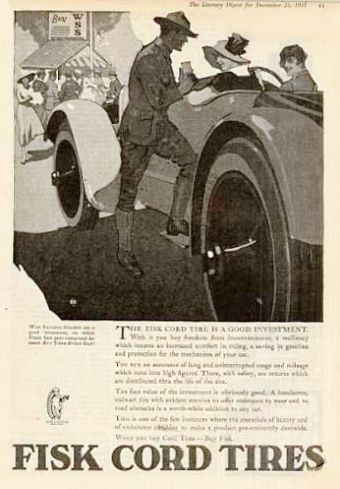

Left and above: Fisk Tire, 1921.

Left and above: Fisk Tire, 1921.

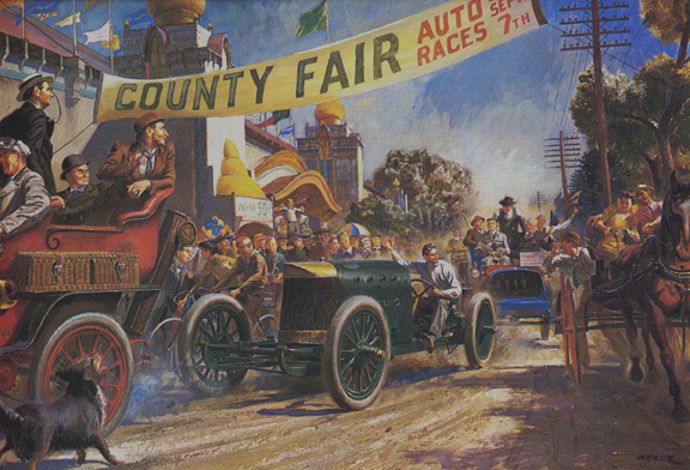

1913The only one of the eight jobs that related to cars was that with automobile press agents Korbel and Golwell. I had won the Poster Competition for the Brooklyn Art Show, and these gentlemen offered me the post of "Art Director" in the advertising agency they had just acquired. Such was the scale of operatlon that the only art direction pertained to my own work, drawings for such forgotten clients as Motometer, Allen Tire Case, others still more remote. However, before my bosses were legally restrained from operating in both press agentry and advertising (deemed as mortal sin), and because of their handling the publicity for 24-hour Racing, various endurance tours and the New York Auto Show, I found myself orbiting in a most agreeable atmosphere. It was cars every minute for the six months I was with K & G. Eight jobs within four years plus increasing outside work had supplied experience and confidence and by 1915 1915 I felt I was ready for freelancing. That Summer I took my Mother to California, and, while attending the lavish Panama-Pacific Exposition, trod those palaced and palm-lined thoroughfares with reverence. Four months earlier the Vanderbllt and Grand Prlze races had run over a circuit within these magnificent confines.

Cause for embarrassment?

Cause for embarrassment?1917

The jump into freelancing had its risks, but I contrived to keep busy with movie posters for Universal Films, furniture drawings for department stores. My brother Henry's

Peter Helck's older brother, Henry J. Helck (1889 - 1973): in later life he was a branch manager for the New York Bank for Savings. He lived in Yonkers, NY, with his wife Sadie and their two children, Bernice & John. Although seldom mentioned in these memoirs, Henry and Peter were extremely close.

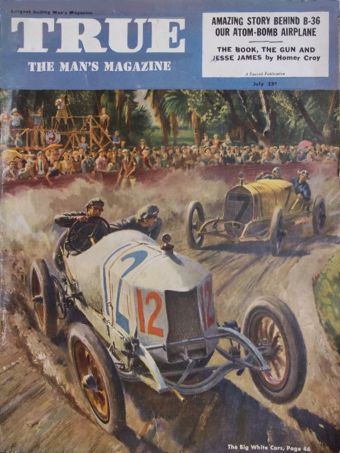

job hours permitted considerable soliciting of New York advertising agencies which resulted in national advertising assignments in the automotive field: Republic Trucks, Exide Batteries. Hoping to climb to the top fast, I submitted a cover sketch at prestigious Collier's Weekly, a portrayal of DePalma's new Mercedes for the Indy "500". As Col. Patterson was the owner of both Colller's and the Mercedes this seemed opportune. Its prompt rejection proved otherwise. 1916Better luck was had with a cover sketch for the new Sheepshead Bay Speedway Program. On rare occasions, unfortunately, one of these covers turns up to embarrass its maker.

job hours permitted considerable soliciting of New York advertising agencies which resulted in national advertising assignments in the automotive field: Republic Trucks, Exide Batteries. Hoping to climb to the top fast, I submitted a cover sketch at prestigious Collier's Weekly, a portrayal of DePalma's new Mercedes for the Indy "500". As Col. Patterson was the owner of both Colller's and the Mercedes this seemed opportune. Its prompt rejection proved otherwise. 1916Better luck was had with a cover sketch for the new Sheepshead Bay Speedway Program. On rare occasions, unfortunately, one of these covers turns up to embarrass its maker.

Fisk Tire series, circa 1917 -- 1919.

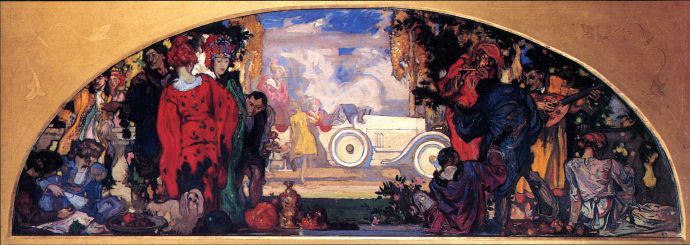

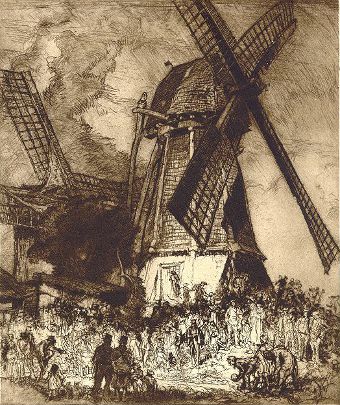

Although my brother's efforts were limited to about six hours weekly, his personality and salesmanship brought substantial results. With our entrance into the Kaiser War he enlisted in the Navy immediately. 1918I did likewise considerably later by which time I did the first of a long series for Fisk Tires. Art Director Burr Giffen (creator of the Time-to-Retire urchin for which he received $10) became a major patron, and this connection portended much for the future. Upon my Navy discharge I resumed with Fisk, and in late 1919 1919was called in to assist on an extravagant project. Fisk had envisioned a series of 24-sheet posters to be executed by the top artists here and abroad. Maxfield Parrish had already finished his. The great British muralist Frank Brangwyn had agreed to do one, but matters were at a standstill as to subject. His first sketches had portrayed a world at war, but now the war was over.

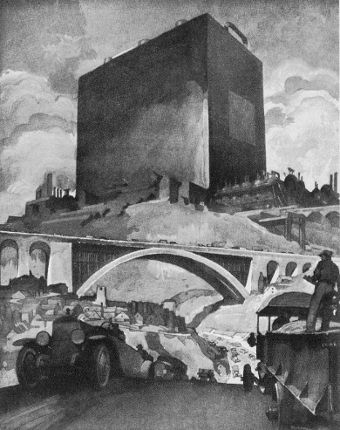

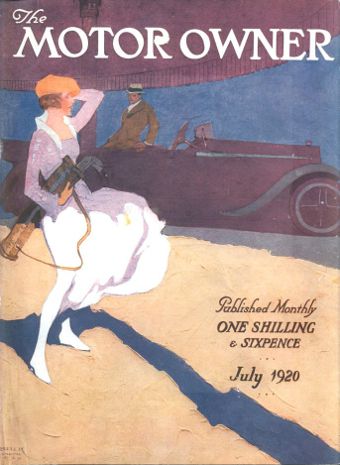

The Motor Owner, London, August, 1920.

The Motor Owner, London, August, 1920.

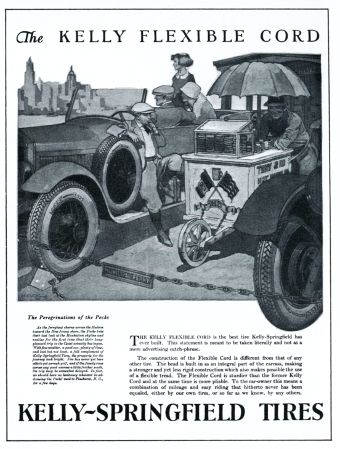

At that time Brangwyn enjoyed great international recognition. Along with most of my fellow artists I marvelled at his genius and still do. I was asked to create a sketch in which the master could employ all the pageantry and riotous color for which he was celebrated and then go abroad to enlist his interest. 1920I found this great man, in the midst of a huge mural, kindly-disposed to American artists. His mural assistants frequently had been Yankees. He had also given private painting instruction to "that American millionaire motor chap"

Charles B. King,

Charles Brady King (1868 - 1957): entrepreneur, inventor and artist. He built the first automobile in Detroit and was mentor to Henry Ford and Ransom E. Olds.

known to all of us. Brangwyn pronounced my sketch as "saucy" and agreed to follow through . . . on condition that I lay it out in full scale in rough form in color prior to taking it on.

This condition would alter my plans, that of serving in reconstruction work in badly shattered France. On hearing this Brangwyn advised, "Reconstruction in France? Rather reconstruct your art, what?" Few young artists could have ignored this advice, particularly as it inferred his interest in my own work and thus just might offer prospect of serving as his mural assistant. Besides, 1920I had fallen in love with London.

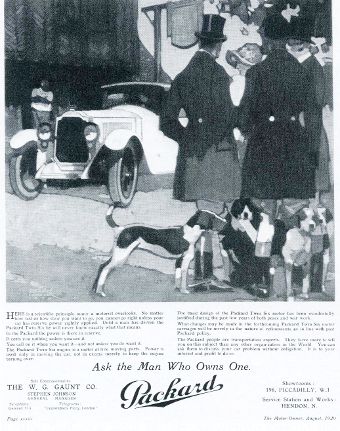

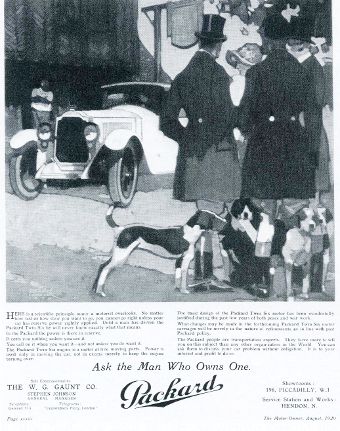

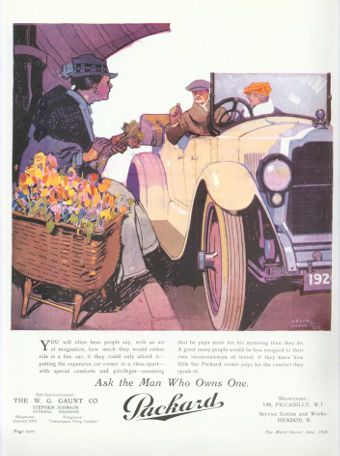

(left) Packard advert, London, 1920. (right) Cover for The Motor Owner, London, July, 1920.

(above) Pen and ink drawing with transparent coloring, London, circa 1922.

(above) Pen and ink drawing with transparent coloring, London, circa 1922.I found

lodgings close to Brangwyn's studio in Hammersmith

Helck's studio was at 93 Brook Green, London W6. Brangwyn's London studio was at Temple Lodge, 51 Queen Caroline Street, Hammersmith

, set about getting the Fisk panel laid out, followed the advice on "reconstructing my art" via much drawing and painting from nature.

The results were always shown to Mr. B, and I profited greatly by his criticisms. I was never happier, but the prolonged stay was diminishing my savings. I decided to solicit work from the publishers of the plush motoring monthly The Motor Owner. Luck was at hand. The Art Editor knew my work. The interview ended with afternoon tea and an order for six full color covers. This publication also serviced its advertisers with artwork and much of this came my way, all in full color, for such firms as Packard, Crossley, Napier, Sunbeam.

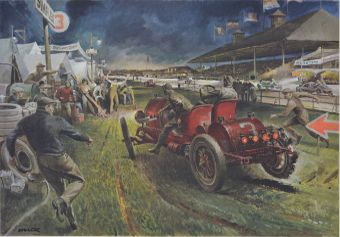

With April came the reopening of Brooklands vast motordome after its wartime siesta. The sight of this enormous arena was breathtaking, more so than most of the racing because of the British fetish for handicapping, a throwback to their equine age. However drivers soon to become world famous were regulars during that season: Malcolm Campbell, Henry Seagrave, Tim Birkin. Already famous as trans-Atlantic flyer, Harry Hawker also joined Brooklands racing elite. The cars offered startling extremes from spidery Gregoires to massive 19-litre hybrids plus a sprinkling of seasoned G.P. Dietrichs, Indy Sunbeams and revamped Essexes. I made trackside sketches from which I developed more finished drawings for that oldest of motor journals, The Autocar. But my most cherished Brooklands experience was as passenger on a ferocious 30-98 Vauxhall driven by Ivy Cummings, the best-known woman driver of that time. In gratitude I made her a small painting of her Vauxhall.

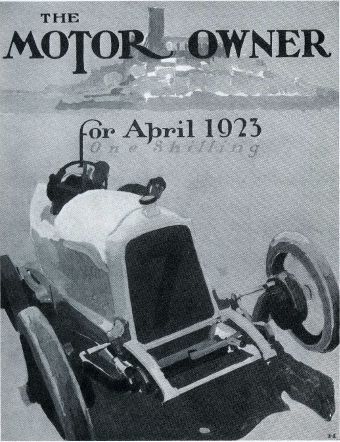

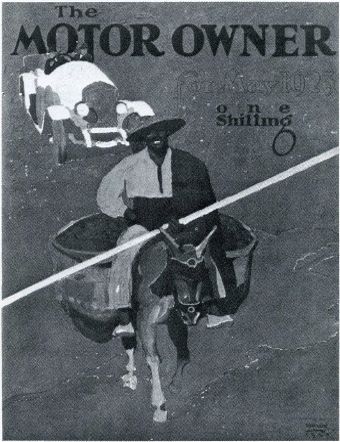

Covers for The Motor Owner, 1923.

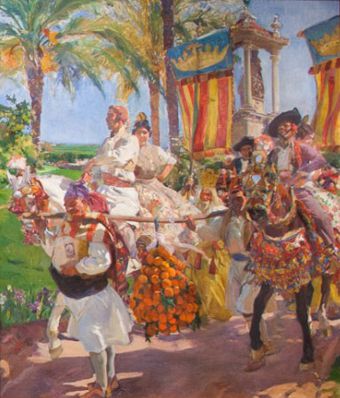

Meantime the Fisk painting hung in suspense, awaiting Brangwyn's wind-up on his mural. But prodding messages from Fisk and plans to meet my mother in Spain induced the master to promise action shortly. This would be at his country place in Sussex. I spent a week with him there, painting landscapes, sketching Gypsies. Only on the final day could I cable New York, "Brangwyn at work on Fisk painting."

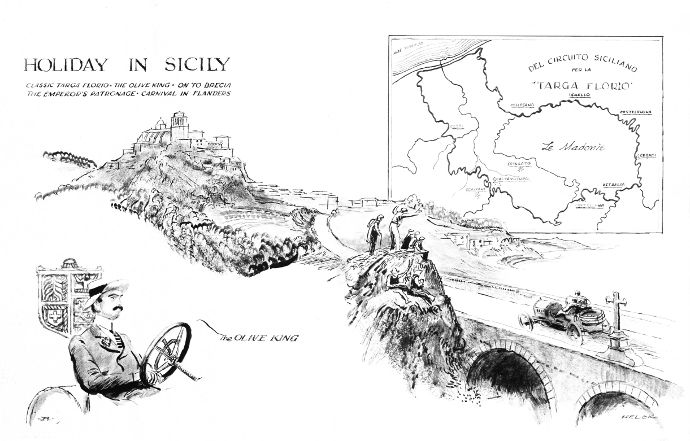

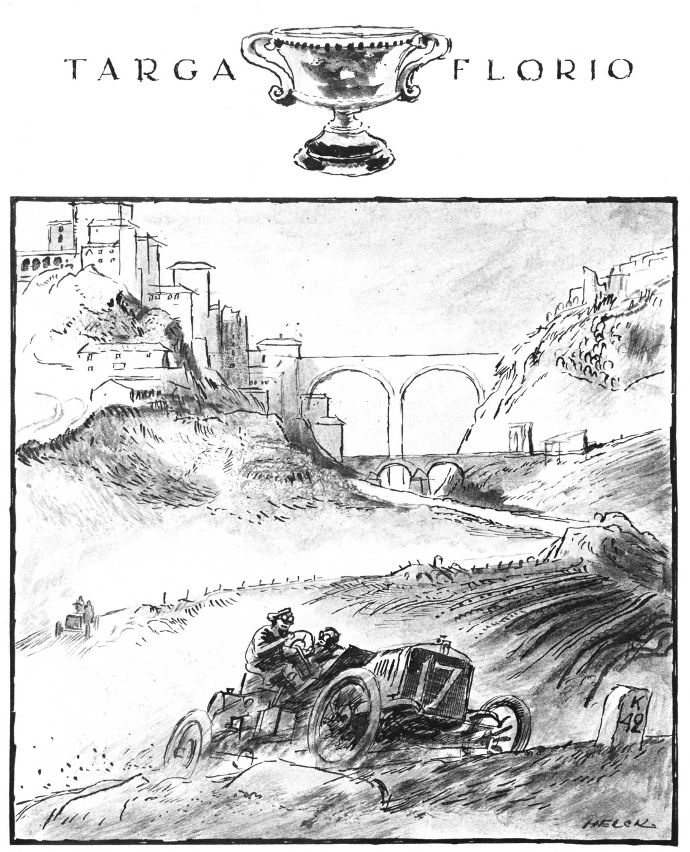

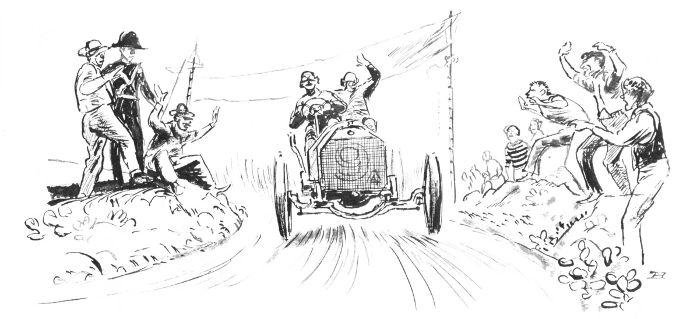

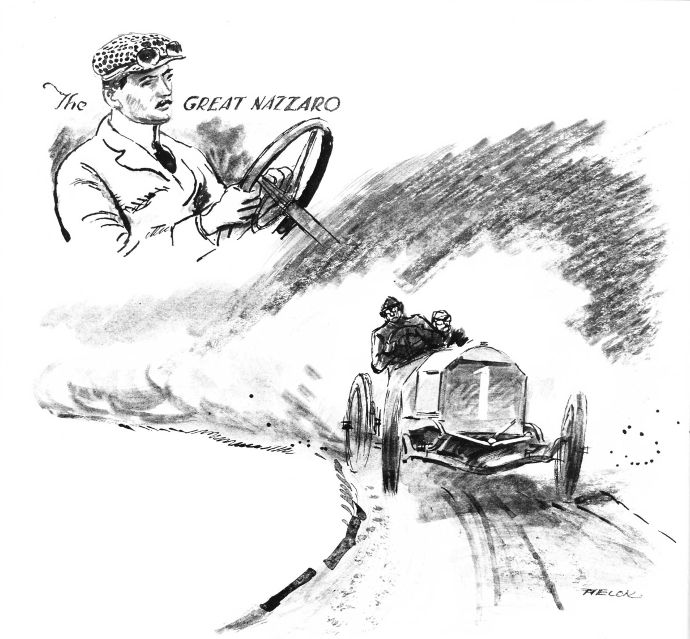

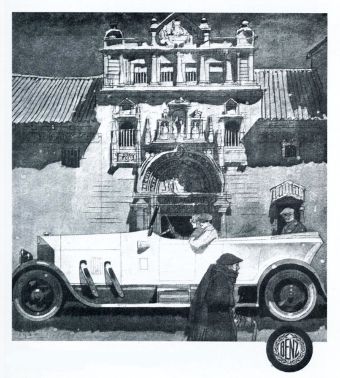

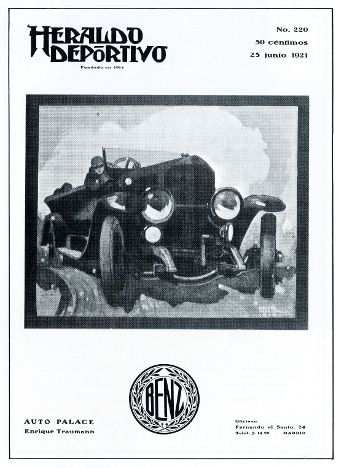

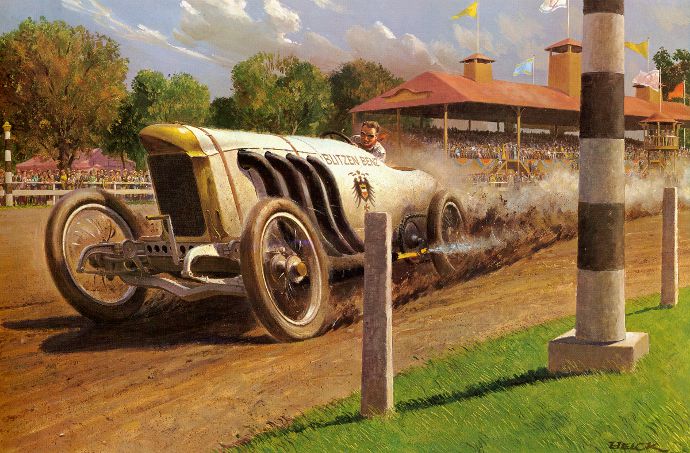

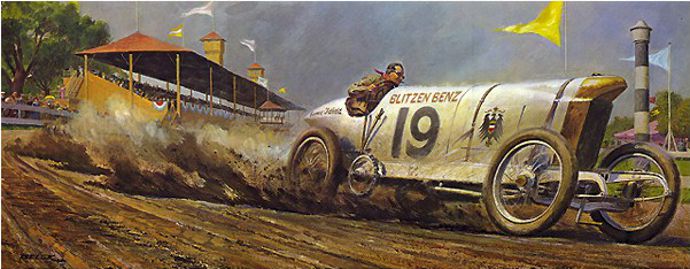

There followed a delightful month with my mother in Spain. After her departure I remained in Madrid, drawing constantly, studying the masters in the Prado, planning further travels. With diminishing funds I sought means of revenue, and, through the kindness of a young Austrian (somewhat mysteriously known as both Herr Taubs and Senor Reyes) who had wide connections, was introduced to Count Enrique Traumann, Benz concessionaire for Spain. For this uncordial personage I made a few drawings for Benz advertising. From other sources I did a series for Gaulois Tires and a full color program cover for the Royal Spanish Opera. This was pretty good going for a foreigner unknowing in the language and it enabled travel to Morocco, Algiers, Sicily, Italy and back to London.

Packard Trucks, London, 1920 and 1921.

Bergougnan Tires, Madrid, 1920.

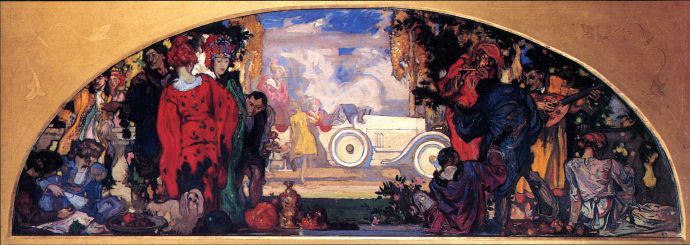

At year's end the Brangwyn painting arrived in New York. I followed shortly and was gratified to see how my thinly-painted "lay-in" had been expanded into a pageant of thickly-applied pigment of exquisite color. All that remained of my contribution was the automobile.

The Fisk Panel

The Fisk Panel1921As a result of the Brangwyn association my interest veered toward mural decoration. A couple of awards at the Beaux Arts for mural compositions gained the post of mural assistant to William DeLeftwich Dodge, a giant of a man whose impressive murals at the Panama-Pacific Exposition had bowled me over in admiration. The job at hand comprised two 12 x 60 foot panels for the Nebraska State Capitol. Dodge's demands upon an assistant were extreme, from daylight to dusk, in studio temperatures frequently near 100. But if he at age 54 could take it so could I, his junior by many years. Upon retiring each night he'd stand at my bedroom door, his huge bulk clad in a nightgown, a burning candle in his hand like a king-sized Fisk Tire Baby and proceed to reminisce about fellow painters and his student days in Paris. Those six months were a grand experience.

Benz advertisemnt, Madrid, 1920.

Benz advertisemnt, Madrid, 1920.

Spain called again, 1923as did England, and now married,

Priscilla Smith Helck (1899 - 1988), originally from Belfast, Ireland, was married to Peter Helck in September of 1922.

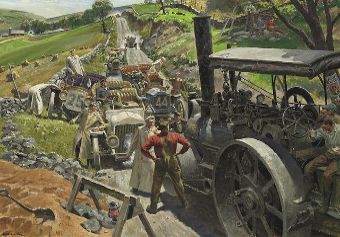

Priscilla and I settled in a studio in Hammersmith. I was painting seriously now, still favored with Brangwyn's interest and encouragement. The way to British recognition was then via the Royal Academy. I submitted three works, one gaining acceptance and given some space in reviews. "pay work" was resumed with full page drawings of London's markets and Cockney characters for the Graphic and Bystander weeklies, and my motor clients were still active. This fact permitted a ten-week tour of the British Isles, my wife, my mother, myself and enormous piles of painting gear crammed aboard a Ford-T tourer. Our single misadventure happened in the only thoroughly unlovely town in Cornwall, St. Blazey. On descending a hill, a horse being driven by an elderly lady took fright. I stood on everything, came to an abrupt standstill, but vital Ford parts were strewn over the road. St. Blazey's only garage and its solitary hotel were owned by the same profiteering gentlemen. This unfortunate coincidence was costly in time and money, and is not, please note, characteristically Cornish. All in all it was a grand tour and a highly productive painting spree.

Benz advertisemnt, Madrid, 1920.

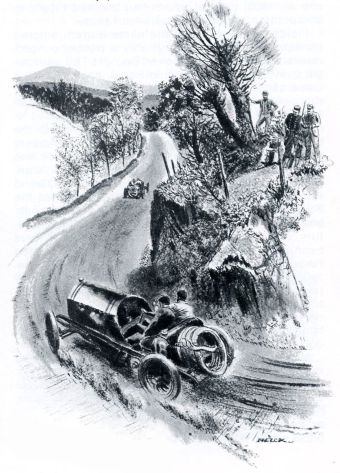

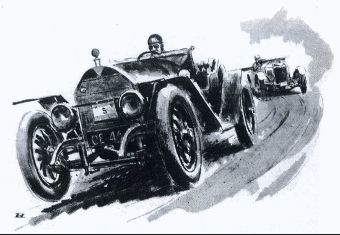

Benz advertisemnt, Madrid, 1920. 1923At Brooklands in 1923 the giant hybrids, often comprising surplus aero engines in vintage frames, thundered spectacularly over the rough high-pitched bankings. Imagine, if you can, a 127 x 178 mm Liberty V-12 power plant of 27,059 cc and a 1907 Benz gearbox nested within an Edwardian chassis, galloping manfully on the straight but becoming an unwieldy fearsome pile of metal on the steep slopes of Brooklands. Such was motor racing in England circa 1923.

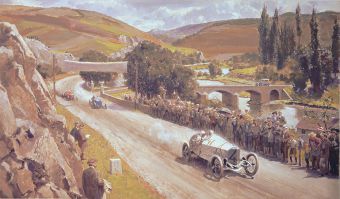

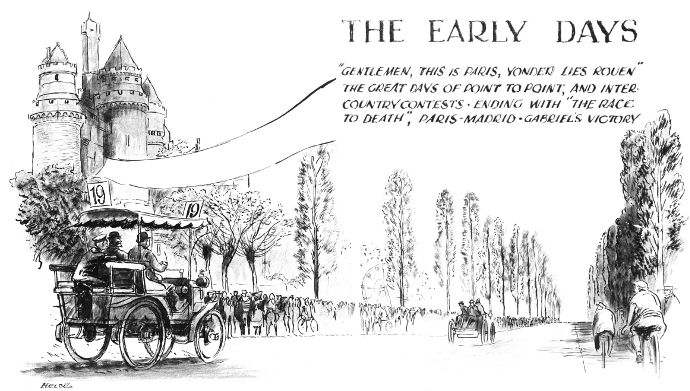

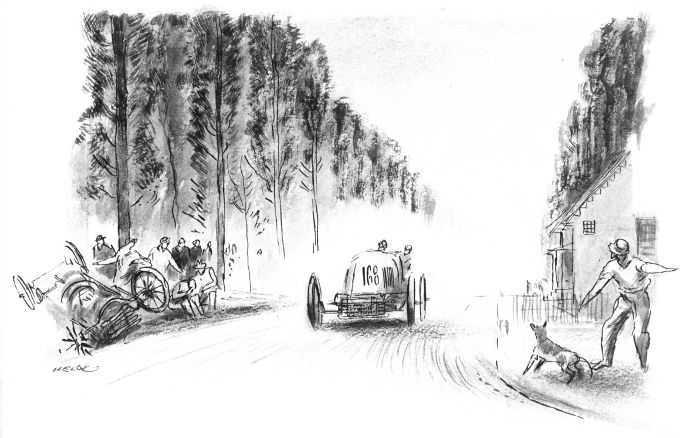

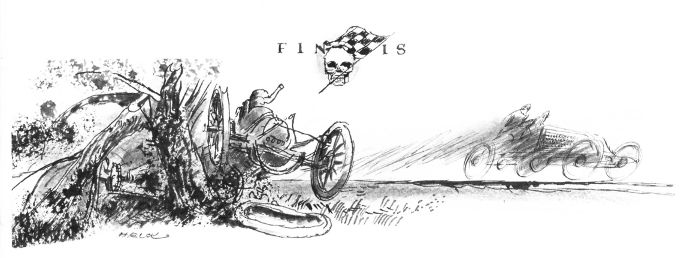

Saner by far was the French Grand Prix at Tours, and memorable also for the sole British triumph in G. P. racing before that exalted designation came in for indiscriminate use. Here Seagrave's 2-litre Sunbeam outlasted the trio of very fast blown Fiats. Here also Voisin and Bugatti entered weirdly-designed machinery, non-conforming in the fullest sense. As a spectacle Tours fulfilled the image of Continental racing as set forth by Jarrott and Gerald Rose in their unforgettable books.

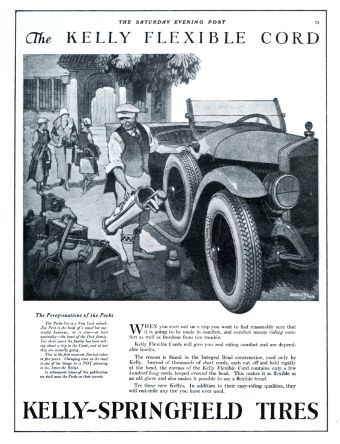

While we were abroad things had happened in New York. The beautiful old

studio building

106-108 West 55th St., NYC.

had been sold to the Grand Street Boys Association, a club of successful men who had fought their way to affluence from the ghettos of New York. 1925I moved to less inspiring quarters in the Miller Tire Building where, amid the pungent fumes of rubber, I did a series of ads for rival tire makers Kelly-Springfield.

(left) Cadillac advert and (right) La Union cover, Madrid, 1920.

In 1926, 1926in harmony with those expansive times, I acquired one-half of the upper floor of an

old carriage house

The studio at 206 East 33rd St. New York City

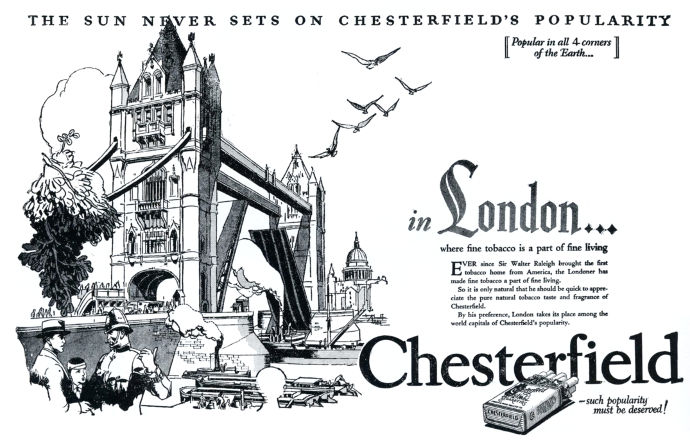

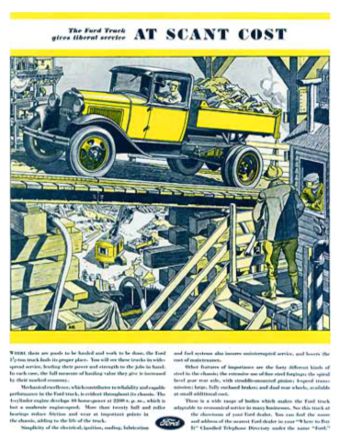

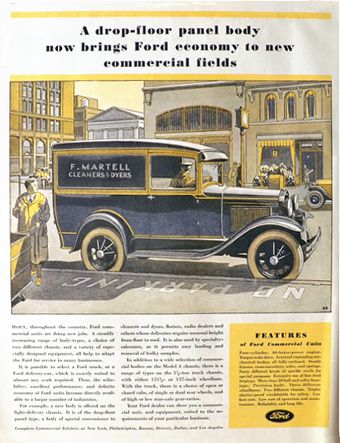

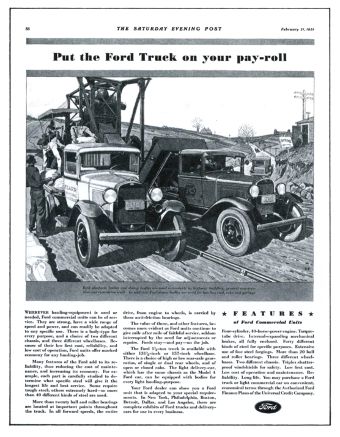

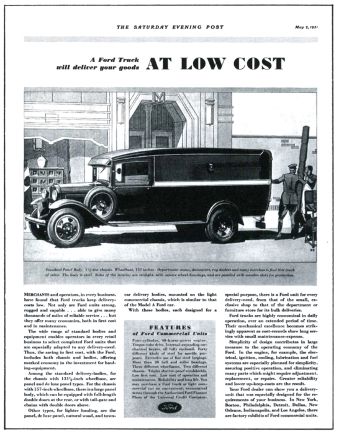

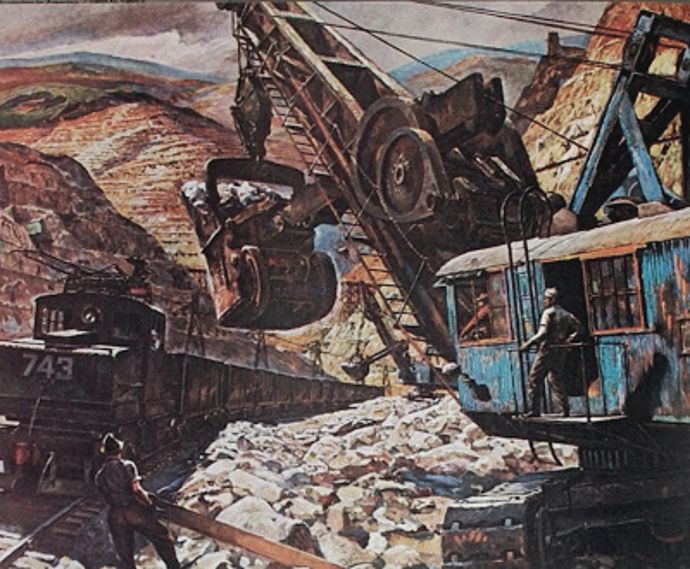

on the East side, and had its 30' x 75' area converted to studio needs. The six years in this grand shop are a cherished memory. Soon I had agreeable next door neighbors, one of them being Dean Cornwell, at that time America's top illustrator and already on his way to becoming equally famous as a mural painter. These were the rocketing stock market days and the contagion afflicted everyone from bootblacks to corporation heads with artists, unfortunately, included. Work was plentiful and clients generous. On occasion an Art Director, well pleased with a job, would phone his satisfaction with, "Pete, that drawing went over big with the client. I'm adding a couple of hundred to your bill!" There was a three-year campaign for Tarvia, another of equal duration for Ford Trucks. There was a terrifying assignment for Canadian National comprising full color paintings, half-tones and line drawings, about 125 pieces in all. The deadlines, necessitated 17 hours a day for several weeks, a long hard pull.

on the East side, and had its 30' x 75' area converted to studio needs. The six years in this grand shop are a cherished memory. Soon I had agreeable next door neighbors, one of them being Dean Cornwell, at that time America's top illustrator and already on his way to becoming equally famous as a mural painter. These were the rocketing stock market days and the contagion afflicted everyone from bootblacks to corporation heads with artists, unfortunately, included. Work was plentiful and clients generous. On occasion an Art Director, well pleased with a job, would phone his satisfaction with, "Pete, that drawing went over big with the client. I'm adding a couple of hundred to your bill!" There was a three-year campaign for Tarvia, another of equal duration for Ford Trucks. There was a terrifying assignment for Canadian National comprising full color paintings, half-tones and line drawings, about 125 pieces in all. The deadlines, necessitated 17 hours a day for several weeks, a long hard pull.

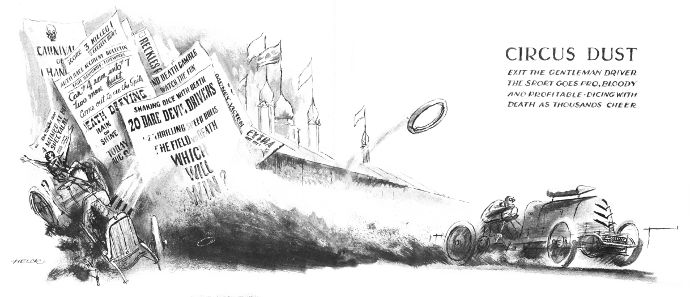

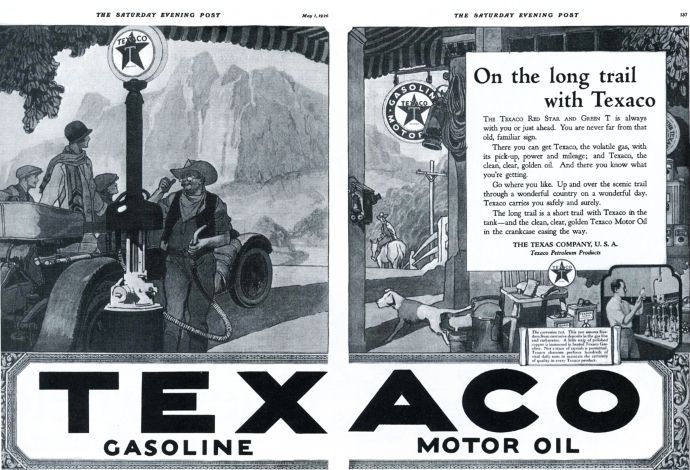

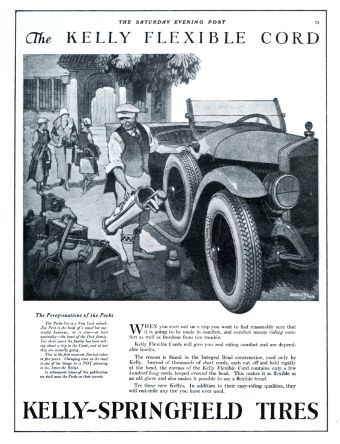

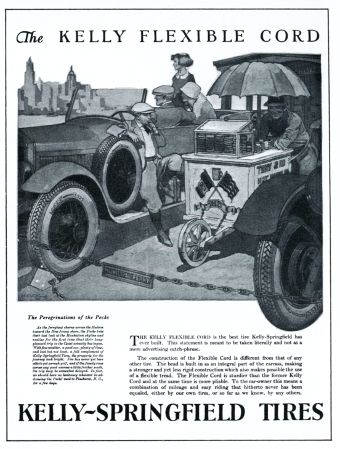

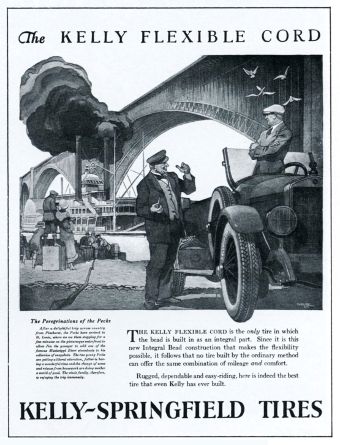

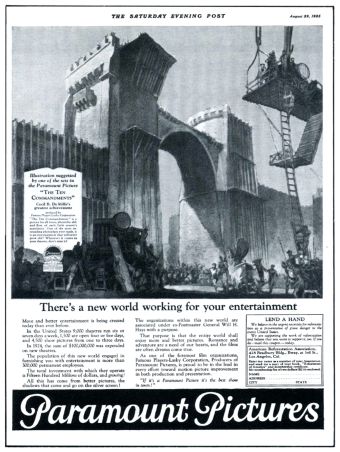

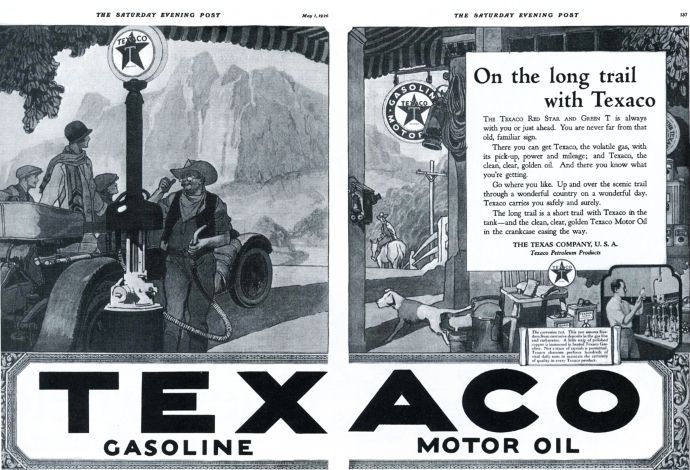

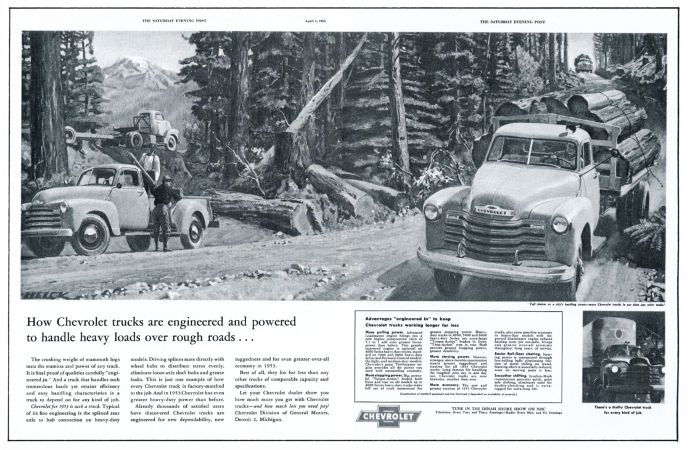

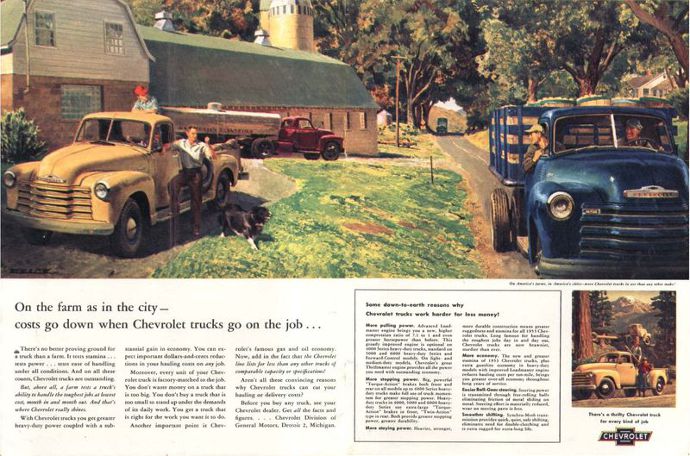

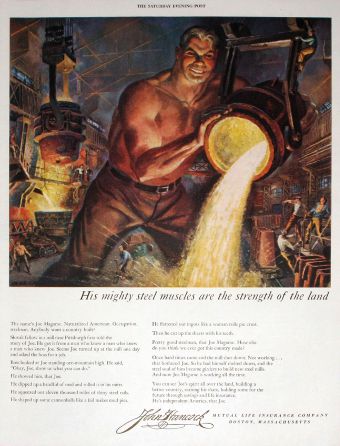

The Saturday Evening Post, March 7 & March21, 1925

The Saturday Evening Post, April 4 & April 18, 1925

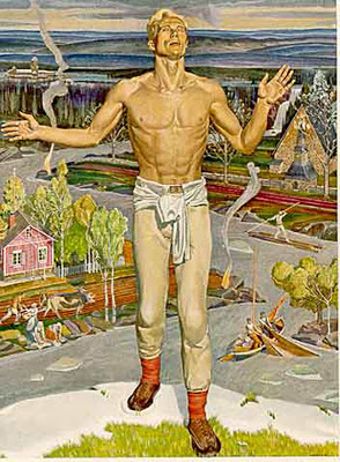

By far the most satisfying commission was for the Steinway Collection which housed the works of eminent American and European artists. I was asked to render my personal interpretation of Sibelius's Finlandia For the single heroic figure I used Gustaf Pierson for the model because of his startling resemblance to the great Finnish runner Nurmi. However, at no time did I dare mention the theme of the painting. Pierson was a Finn-hating Swede!

(left) Finlandia for Steinway. (right)The Saturday Evening Post, August 29, 1925.

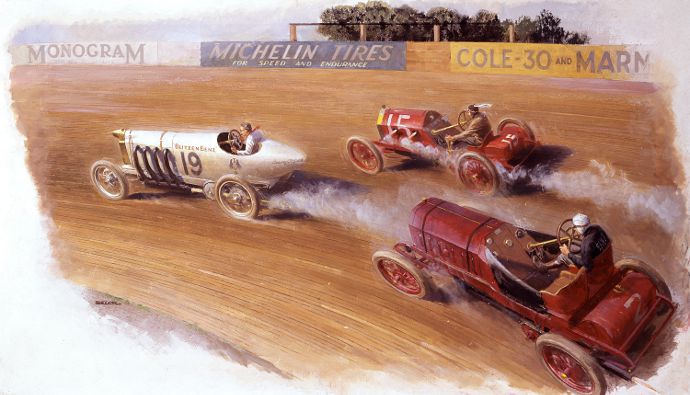

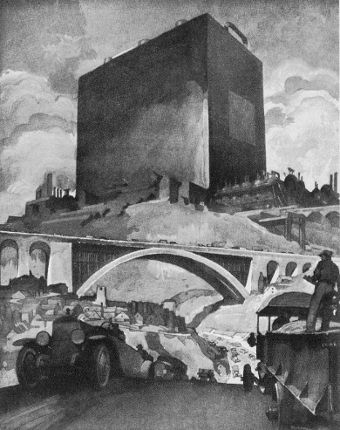

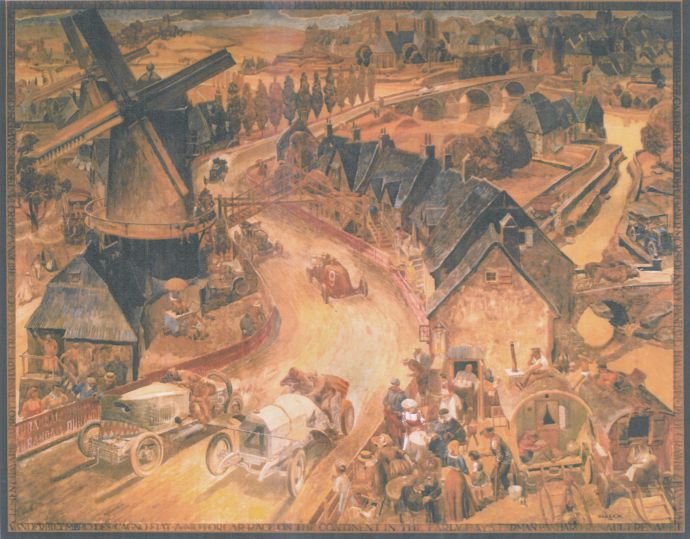

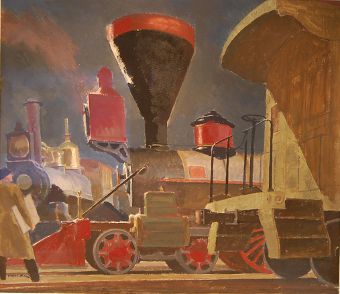

This was done for my self-gratification in 1926 and is the painting that appeared in Fortune in its first year of publication. I'm quite sure that Henry Luce thought the fee of $100 excessive. It measures about 4 x 5 feet, was rendered with Martini tempera, and was shown in several exhibitions.

This was done for my self-gratification in 1926 and is the painting that appeared in Fortune in its first year of publication. I'm quite sure that Henry Luce thought the fee of $100 excessive. It measures about 4 x 5 feet, was rendered with Martini tempera, and was shown in several exhibitions.

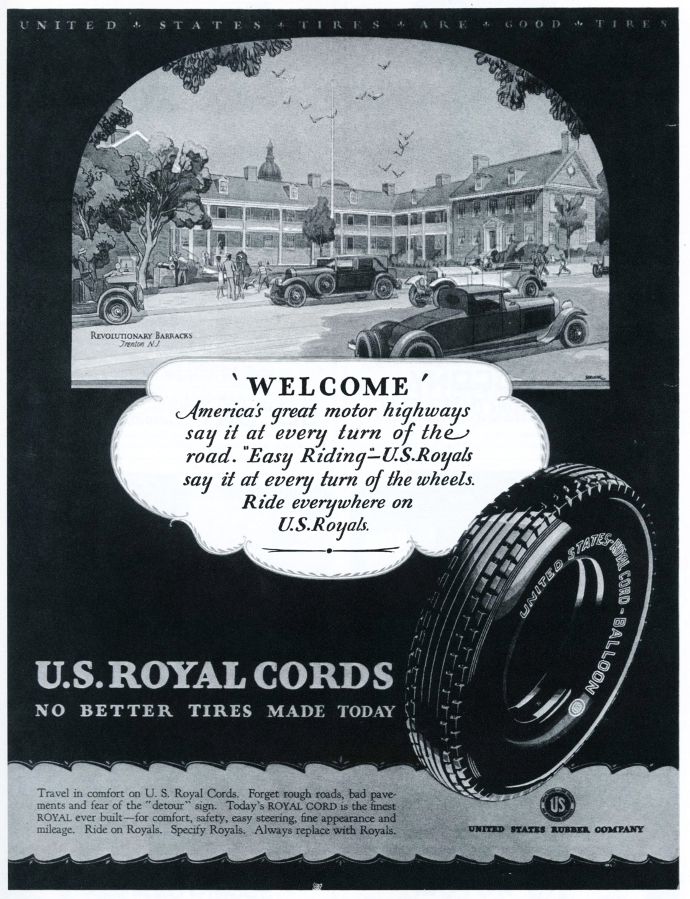

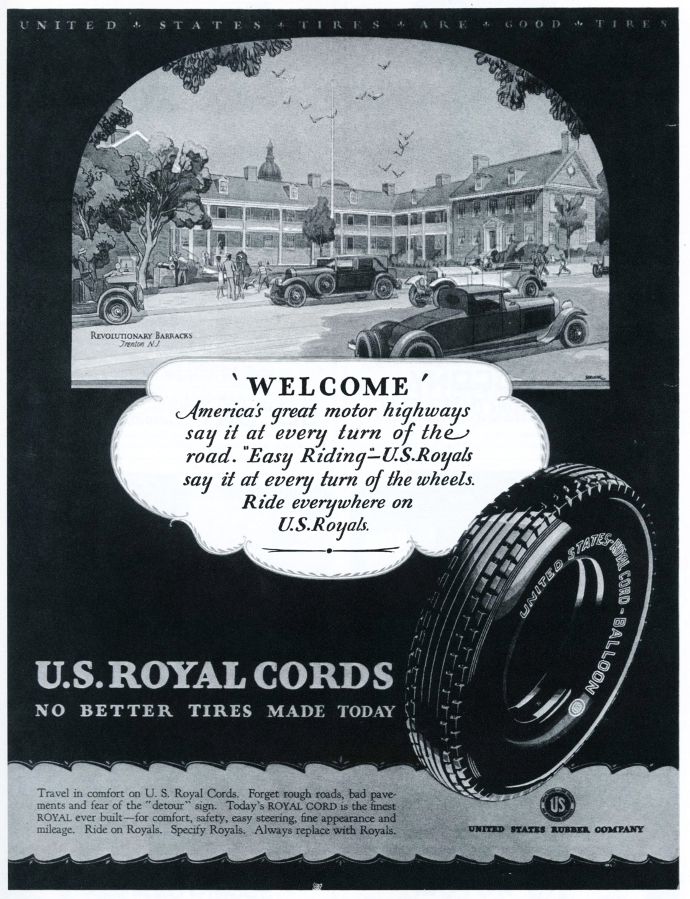

The Old Barracks, Trenton, NJ (U.S. Royal Tire Ad) The Saturday Evening Post, August 18, 1928.

The Old Barracks, Trenton, NJ (U.S. Royal Tire Ad) The Saturday Evening Post, August 18, 1928.

1927My good wife Priscilla and I went abroad in 1927 and traveled in Italy extensively with a lovely little 509 Fiat Tourer. The means by which a driving license was acquired in Rome was profoundly devious. We were advised by a linguistic courier that "the man to see" was Signor Clemente Paoli, an elevator operator at the Court of Justice. With extreme misgivings I followed instructions and turned over passport and other credentials to this jolly little gentleman during a "conference" in his elevator between the third and 4th floors of the Court House. The constant buzz of impatient would-be passengers, some of them black-robed Justices, was completely ignored during our informal transaction.

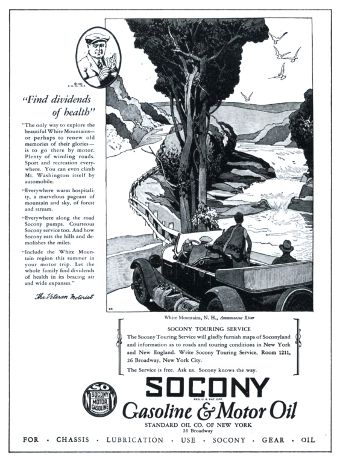

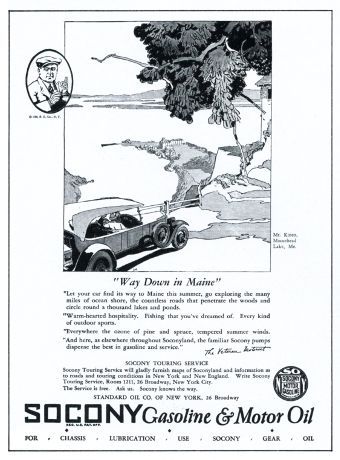

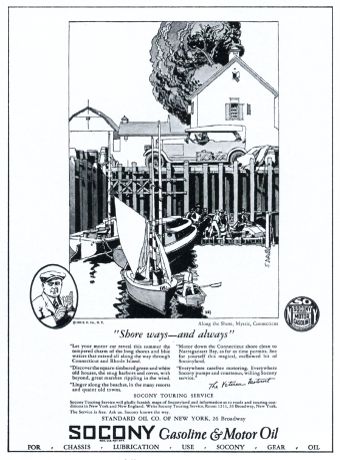

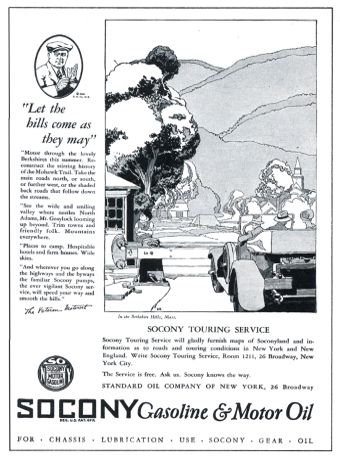

Series for Standard Oil of New York, 1926.

The following morning I returned by appointment, was given a "Driving Test" in the office of a harassed office clerk, said test being made while seated in a chair where I demonstrated the flexibility of my feet for pedal action and the firmness of my grip on a steering wheel. I passed with honors. Matters were squared with buoyant Clemente, my personal papers returned, and our tour got underway.

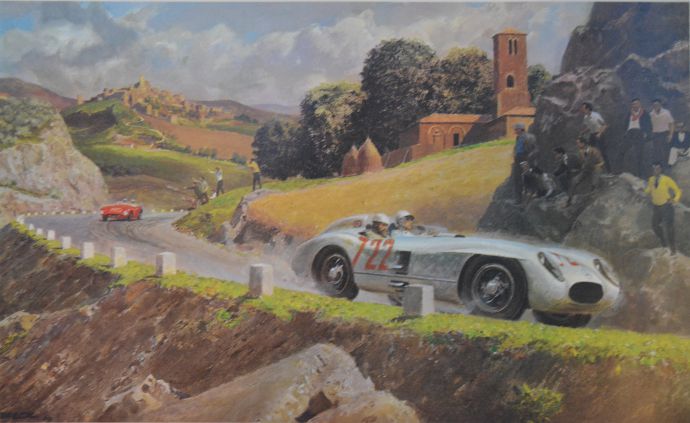

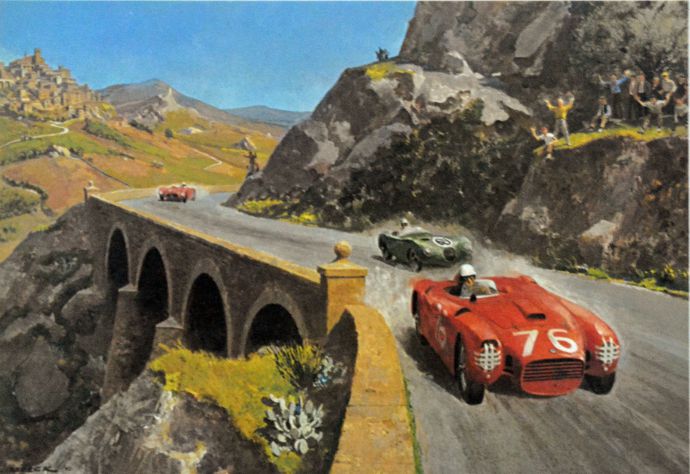

Painting the grand landscape was the number one objective, but motorcar interests were to be enriched also. We were in time for the first running of the great Italian annual, the Mille Miglia, and became immediately aware of the hazardous conditions under which this race was conducted. The roads were not closed. Normal traffic, although warned, was not restrained from using them. As for the spectators, here was the same disregard for safety as had prevailed at the old Long Island Vanderbilt Races, only more exuberantly displayed. The roaring O.M.s, Fiats, Alfas and Italas, skimming miraculously past wine carts, sedate limousines and the intruding crowds, were we soon learned, completely in character with Italian highway deportment.

American Book Company calendar, 1927.

American Book Company calendar, 1927.En route to Milan we spied a sleek red P-2 Alfa sparkling in the sunshine at a filling station. Our interest in this beauty effected an invitation for a spin from the prideful attendant. I'll never forget the terrific impulse of its acceleration, or its deceleration either. After the exciting ride the driver proudly removed the seat cushion I'd been sitting on, pointed to some faded blood stains, and disclosed that the ex-owner had perished in an appalling crash with this car!

The New York Telegram, July 26, 1927.

The New York Telegram, July 26, 1927.As Monza's famed circuit could be traversed for a slight fee we took the little 509 around for a few laps. Loaded with luggage and painting materials, we managed to get the needle up to 100 kil. But we were not always that volant. Once on a long upgrade in the Abruzzi Mountains the engine sputtered then died. We were out of gas. Daylight was fading. A group of small boys offered advice, unintelligible to us. Suddenly we heard the healthy roar of an approaching car ahead. It topped the crest of the grade as can only Alfas driven by audacious young Italians. He pulled up with a screech, having noted my good looking wife, and another "transaction" was underway. Alfa petrol was drained, bottle by bottle, into the tank of the Fiat. In gratitude we insisted on presenting our rescuer with a quart of Spumante. Off he went with a wave and a roar. But before we reached the next town, a mere mile from the crest, we were again in trouble. It took the next morning to cleanse the Alfa's dregs from our fouled feed lines and carburetor!

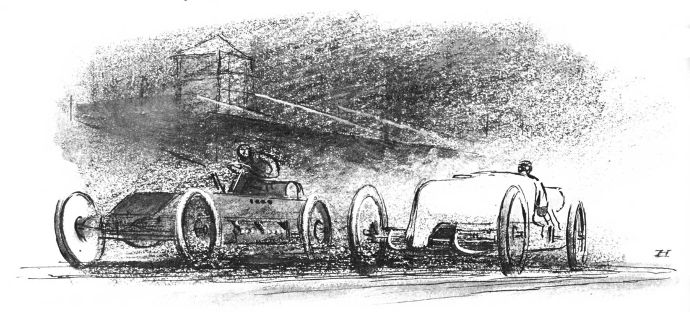

The Saturday Evening Post, May 12 & May 26, 1928

Back in New York Coolidge Prosperity and those "good times" still prevailed. Pay work was now shared with serious painting. I was sending to exhibitions, winning a few awards, had a couple of oneman shows of landscapes and portraits and resumed study in private classes at night.

While1930 - 31 engaged with the Ford truck campaigns the weirdest sort of coincidence threatened the cordial relationship I enjoyed with N. W. Ayer, Ford's advertising agency. One of the pictures, to be rendered in two colors, purple and black, had to show a Ford van unloading at a swank cleaners and dyers in a smart suburban town. I chose Bronxville, New York, then as now filling these qualifications. While sketching suitable store fronts I encountered an old high school mate. Past incidents were recalled, old friends discussed. I asked, "What ever became of that big footballer Mittell?" He told me enough for that name to stay in mind for several days. With the drawing near completion I considered adding the name of a firm on the van's polished panel, hit on the name of the footballer Mittell but discarded it as being overly Teutonic. The derivation, F. Martell, looked and sounded more like fashionable suburbia.

Two months later N. W. Ayer phoned. Had I seen Walter Winchell's column? I replied I never read his stuff. "Well, read him this morning" was the advice from Philadelphia. "Then call me back." Winchell had written about as follows. "Perhaps the artist responsible for the Ford Truck ad in the current issue of the Saturday Evening Post had his tongue in his cheek, but it is no laughing matter for the widows and orphans of those slain in the Purple Gang warfare involving Detroit's cleaning and dying industry." He further disclosed that the Purple Gang leader was a notorious racketeer serving time; his name, F. Martell.

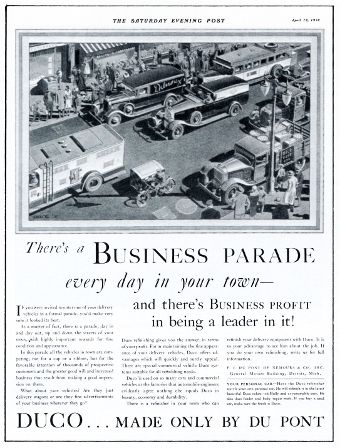

The Saturday Evening Post, December 6, 1930 & January 24, 1931

There were a few worrisome days for all concerned in Ford advertising, but my explanation was accepted and I continued to work on the series. As expected, Winchell failed to print my explanation. Not much later the great man's chauffeur-driven limousine very nearly clipped me while I was crossing West 50th Street.

The Saturday Evening Post, February 21 & May 2, 1931

While occupying the stable studio I came to know personally one of my boyhood idols, Joe Tracy of Vanderbilt Cup fame. Before becoming aware of his devious skills in practical joking I gladly accepted his invitation for a weekend of camping in the Poconos. Fortunately not for a longer period as it proved to be 48 hours of misery. I met him at his laboratory in Rutherford a few minutes after the appointed hour. H is displeasure with this tardiness was undisguised. He then prepared to lash several lengths of 2 x 4 beams between the fenders of my DuPont convertible, apparent necessities for our camping expedition. Upon my mild protestations the stuff was returned to the lab.

Upon setting off I was instructed to follow closely his guidance through the towns en route. His Chevrolet Coupe had accelerative capacity well above that of the DuPont, but I did my best. I was close enough to observe the old boy lifting a canteen to his mouth, then turn his head to the left and eject a spray which smacked against my windshield. The wipers were useful for several miles. I followed my guide into a busy town. As the Chevie exited at the far end, I was stopped by the police for running the wrong way on a one-way street. By the time I had eased out of this situation my host was in foot-tapping impatience because of the precious time lost.

The Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1930

The Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1930On arrival at the campsite at dusk, a bleak windy spot, my ineptitude in rigging tents was obvious so I was assigned the task of placing our provisions in "the only safe place around here" the branches of a nearby tree. I had hoped to hear lengthy reminiscences of his racing days but boyhood hero was sullen and uncommunicative. Then in Indian fashion we followed a trail through the woods where every footfall on the blanket of old leaves made conversation impossible. Mr. Tracy now became highly eloquent and also highly annoyed with my repeated, "I didn't get that."

I was awakened after a miserable night on the hard ground by stones hitting the canvas. "Wake up, man," came the command "You've got to see the sunrise." The weekend was survived. I arrived home completely exhausted, also bewildered. Tracy's "short cut" directions for returning to New York had added miles to the trip. Nevertheless we became fast friends but all future camping invitations, offered with a smile, were just as amiably declined.

Painting for Packard advertisement which ran in The Saturday Evening Post, October 8, 1932

Painting for Packard advertisement which ran in The Saturday Evening Post, October 8, 1932Thanks to Old Joe I learned of the whereabouts of his old racing comrade, the young Simplex tester from 96th Street days, Al Poole. Meeting him again after 20 years was the renewal of a firm friendship lasting until his death in 1959, seven months after that of Tracy.

1929Came the Crash, the end of the phony prosperity, shortly to eradicate security for millions. My own work continued for a spell, then dropped off gradually. 1932Having purchased a farm in the country needing costly renovation of house and barns, I felt the need of giving up the spacious East Side studio for a less expensive one on 47th Street. In company with so many others, our investments were sadly shattered.

During the boom years a few old cars had been acquired; sounder investments by far than the so-called securities of that day. These consisted of a 1904 chain-drive Mercedes with an unsympathetic 1915 White touring body; a 1907 Renault Town Car which had belonged to Albert R. Shattuck, past President of the Automobile Club of America. The Mercedes today, fully restored with authentic coachwork, is owned by likeable VMCCA Member Roland Beattie. The Renault, due to Joe Tracy's persistent efforts on behalf of the Thompson Products Car Museum, is now in that Collection's present plush environment. For those interested in inflationary trends, I think the Mercedes cost $200, the Renault $75. Another purchase at that time, a Mercedes-Knight Tourer of 1921 (still ours) cost $500.

Of my 47th Street Studio I remember only that it was too small, that I had no immediate artist neighbors and that the ground floor premises were occupied by a benevolent institution, The Opportunity Shop, where donated merchandise was offered at very low figures. The Depression was at its worst. The Bank Holiday was on. Even the non-profit Opp Shop was feeling the stress. Its Manager knew of my interest in early cars. Was I interested in an elegant Brewster Town Car at $100? I felt obliged to decline. Apparently no on else had $100 to spend so recklessly because this good chap would appear from time to time with easier terms', $75, then $50! On the fourth occasion, at $35, I decided yes. I still recall his smiling rebuke, "You chiseler," justifiable perhaps from his point of view.

1934With improving conditions, a far better studio was leased on

East 53rd Street

10 East 53rd St. NYC. Helck occupied this studio until the 1960's.

opposite Mr. Winchell's hangout, The Stork Club. Shortly after locating here and while having lunch with my wife and old friend

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell (1892 -- 1960): American illustrator and muralist.

, the latter mentioned his forthcoming trip to Italy for the purpose of studying the Florentine frescoes preparatory to a mural for which he had been commissioned. "Any chance of coming along?" he asked me. My understanding wife replied "Why not!"

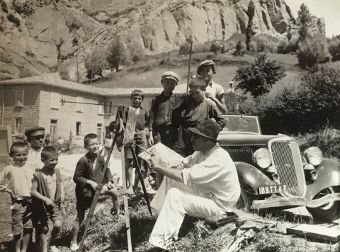

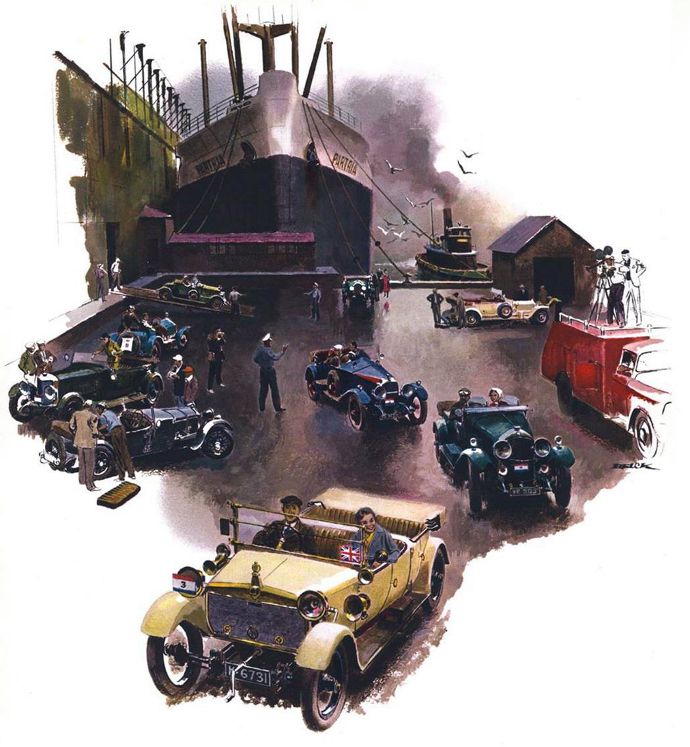

And so it came to pass that Dean, his V-8 Ford Convertible and myself sailed to Europe. We docked at Liverpool, the car going on to LeHavre. We spent a happy day with Brangwyn (now Sir Frank) in Sussex, thence on to France to collect the V-8 for a few days in Paris prior to Italy.

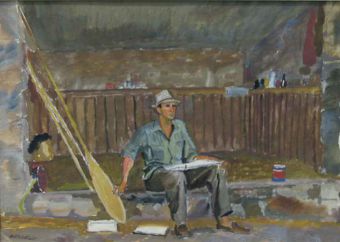

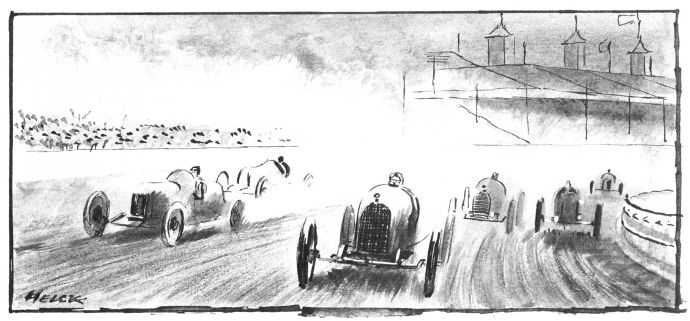

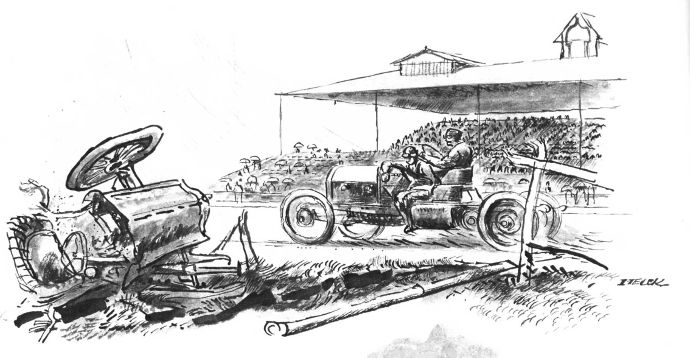

Dean Cornwell painting in Italy

This pause permitted attending the LeMans 24-Hour Race during those magic hours from dusk to the blackness of night. Britain, as so often, supported this event liberally, this time with 23 entries consisting of squads of Rileys, Astons, MGS and Singers. Opposing were 17 French starters and a handfull of Alfas from Italy, two of the latter in the hands of topflight Britishers. Drama is always to be had with fast cars crashing through the night, and at LeMans is the extra bonus of the carnivalesque. But for this viewer, then and again in 1951, deep gutsy enthusiasm was lacking. I've painted the subject three times, never with marked gusto. Certainly the finest cars and pilots evoke the plaudits of tens of thousands year after year, and no one views their astounding mileages as less than miraculous. Above 2800 miles now! For me the old Twice-Around-the-Clock grinds at Brighton Beach and Morris Park where anything between 1000 and 1250 miles was record-going had higher appeal, historically and sensually.

The frescoes in Florence held Cornwell's attention for ten days. My interest was the dynamic landscape further north in that mountainous area just south of little San Marino, the mountain Republic. Thus the V-8 was generously turned over to me and I put up at a miserable little (and the only) hotel in Novefeltria. Here and in the grand neighboring hills I painted every daylight hour, awakened each morning by operatic arias sung by the town's street sweeper. Poor old man. In time he was forbidden to fill the morning with song and promptly died!

Friendships were made among the locals, three of whom had once lived and worked in the United States. All longed to return, but Mussolini was not letting potential soldiers out of the country. In fact, during my stay and unknown to me had been the crisis of

Brenner Pass

This is probably a reference to the "Austrian Crisis" in July 1934 when Nazi agents assasinated Englebert Dollfus the Chancellor of Austria. Mussolini was nominally supportive of Austrian independence and the Brenner Pass was the route that Italian troops would have used to enter Austria.

. I was aware, of course, of the army contingents that suddenly occupied Novefeltria, but did not know the significance of this mission.

One day, while painting on a hilly roadside, a corps of Bersagliere came pumping up the steep grade on push-bikes, their faces flushed and sweating under gasmasks. Zipping past them in a cloud of dust was an officer and his driver on a motorcycles sidecar combination. Upon spotting me the cycle was brought to a throbbing standstill. I'll admit to some misgivings when the officer approached, but was immediately relieved on being addressed in English and learning about his own painting aspirations. Apparently there was nothing suspicious about a foreigner sketching in this area of army occupation. During our amiable chat, with heavy armored vehicles now grinding up the grade and supplying a more purposeful aspect to these maneuvers, the sidecar driver was contentedly picking flowers in the nearby field.

When leaving this paintable countryside to join Cornwell in Florence, my new-found friend Umberto came to see me off. As the Ford was being refueled for the journey over the Passo del Muraglione Umberto reported the comment made by the man at the pump. "He says he is so sorry to see you go away. He likes your car because of its eight thirsty little cylinders!"

Economic conditions at home were improving and upon my return time was shared with advertising, magazine and exhibition painting. My first love, steam locomotives, got a hefty renewal at the 1939World's Fair where the finest examples of this species, past and present, were beautifully displayed. I did a set of tempera paintings when these mammoths were made even more impressive by the floodlighting at night. These were given a one-man show at a Fifth Avenue gallery. None sold. I gave a few to admiring rail fans and was prepared to present one to that excellent railroad historian, the late Lucius Beebe, but his critical inspection of these works evoked nothing but profound silence.

(left and above) 1939 New York World's Fair

(left and above) 1939 New York World's Fair

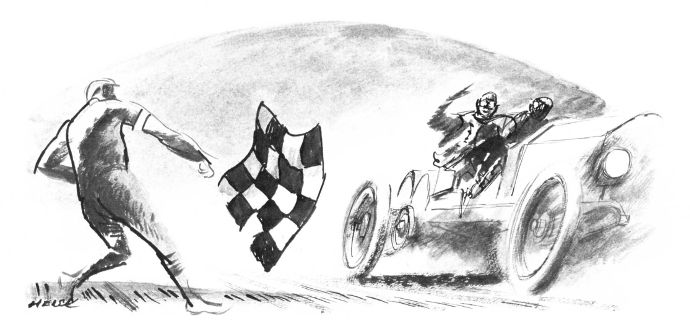

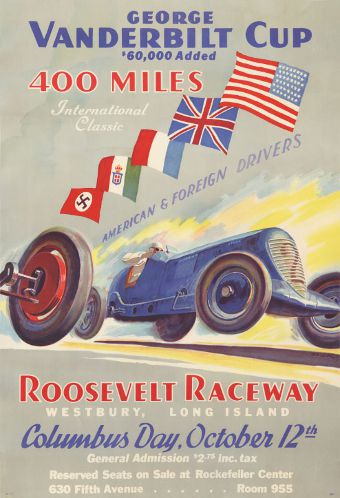

Nearing completion now was the fabulous Roosevelt Raceway where Vanderbilt Cup Racing was to be revived. 1936I hoped to be of some use in designing posters or program covers but was given a brisk runaround at Steve Hanigan's press bureau. I decided to try the Raceway's General Manager, the man whose dream of revived Cup Racing was at a point of realization, George Robertson, the Vanderbilt winner of 1908. He was not exactly displeased upon learning that I had seen him in this race and many others, but was enormously surprised and delighted to know that his old Locomobile No. 16 still existed. He had long believed it forever gone.

This brief interview began a lasting friendship. It also inspired the Raceway to contact the owner of the Loco,

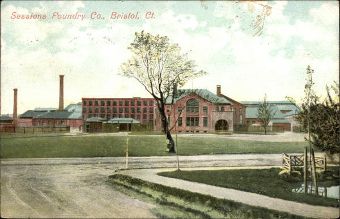

Joseph Sessions

The Sessions Foundry in Bristol, CT, owned by Joseph Sessions, made many of the castings used on the Locomobile race cars.

, foundry man of Bristol, Connecticut. Arrangements were made for a one-lap exhibition run just prior to the start of the revived Vanderbilt. The interview also resulted in my doing a poster and other jobs for the two Cup Races, 1936 and 1937.

, foundry man of Bristol, Connecticut. Arrangements were made for a one-lap exhibition run just prior to the start of the revived Vanderbilt. The interview also resulted in my doing a poster and other jobs for the two Cup Races, 1936 and 1937.

Robertson did indeed drive that exhibition lap and then wondered how he'd been able to "handle the brute" for four hours at high speed 28 years before! But the revival was no howling success. Because the pretzel-like pattern of the circuit demanded moderate pace, sports writers commented caustically about the mild mph achieved by the world's top participants. This speed, said they, was uniformly bettered by the customers who drive to the race in their own cars.

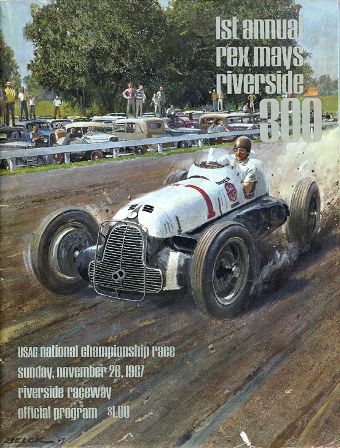

By 1937 1937the circuit had been greatly simplified, permitting 160 mph and above on the finishing straight. Unlike the Italian triumph of Nuvolari and Alfa the year before, this race, signifying the German takeover in classic racing, was won by Rosemeyer's Auto Union with Seaman's Mercedes a close second. As before, our contenders were nowhere although Rex Mays's 3rd place in an elderly 8-C Alfa gave a degree of comfort to American enthusiasts.

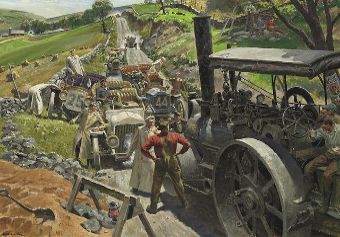

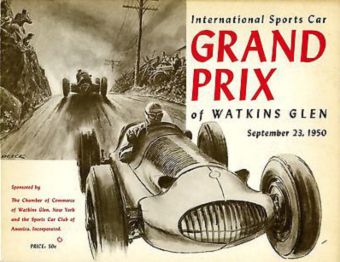

1934I think it was at about this time when a hardy group of young amateurs, the Collier brothers as prime movers, organized the Automobile Racing Club of America, later SCCA, and staged a so-called Briarcliff Race Revival. This was run over semi-private roads not too distant from the 1908 Briarcliff circuit. In spite of the few entries and the varied concept of what constituted sports car machinery (Rileys, Austin 7s, souped-up Overlands) these backyard G.P.s were spirited entertainment and initiated the trends that were realized at Watkins Glen a dozen years later.

My work in advertising art had by this time won the Harvard Award for an industrial series for Westinghouse; four Art Directors Medals in New York and similar top awards in Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland and Chicago. Now less time was given to work in the fine arts field. Sales in this category continued to be negligible. Besides, many of the new trends were a complete divorce from tradition to which my loyalty, wisely or not, was firm. I still believed in Brangwyn's edict "Go to Nature" so there were painting sprees locally and in New Orleans, Texas and Arizona, shared by my ll-year old son Jerry who displayed very promising talent.1941 However, as fine as it was, this Southwestern landscape thrilled me far less than had the mountainous regions of Spain and Italy.

Life magazine inside front cover, March 7, 1938

Life magazine inside front cover, March 7, 1938 The Saturday Evening Post, October 22, 1938

The Saturday Evening Post, October 22, 1938

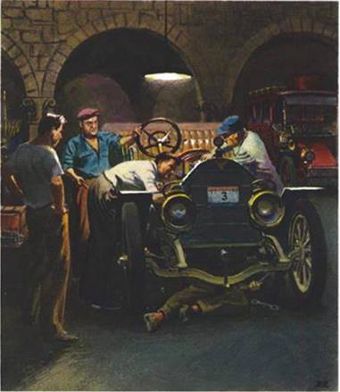

Joe Tracy was now a frequent visitor at my New York studio, and he conducted some of his consultation and research projects at this address. Time and again he proposed we visit Mr. Charles B. King and other early-day auto personages, but my preoccupation with work prevented. I responded promptly, however when Joe suggested we run up to Bristol, Connecticut and have a look at the old Cup-winning Locomobile. We were cordially welcomed by Mr. Sessions and led to the nest-like garage built expressly to house the veteran. Legend told of the proud owner's annual spin, the annual ticket for speeding and the twelve-month recess prior to the next penalization. The car was in excellent condition, and its existence prompted inquiries about the fate of the sister car, Tracy's reserve in the 1906 Vanderbilt and first in the 1908 running when driven by Joe Florida. Sessions believed its l6-litre engine had been installed in a boat and the chassis scrapped. Thus No. 16 was the sole survivor of the three racing specials designed by A. L. Riker for big time racing. The first, with a 7 x 7 power plant and built for the Gordon Bennett and Vanderbilt of 1905, had long since passed into oblivion. The fate, alas, of too many automobiles of historic worth.

The advent of the three major clubs, VMCCA among them, was the first significant step toward the preservation of early cars. Prior to this there had been far-sighted sentimentalists dedicated to rescuing forgotten relics. As early as 1936 George Waterman, Kirk Gibson and Paul Cadwell (all founding fathers of VMCCA) had already accumulated 200 antiquities. But it was the clubs, their publications and their meets that fertilized a minor hobby into a nationwide fanatical interest.

The date of my VMCCA membership is vague, nor can I remember the date on which I attended my first meeting of the New York Chapter. But I do recall vividly the warm greeting extended by Alec Ulmann, Dean Fales and Leslie Gillette. Perhaps the attendance was less than twenty, but the fraternal atmosphere was immediately evident, and one may be excused for stating that with the fantastic growth of our clubs much of the intimate companionship has faded. I never had the wish to serve officially in club affairs, but I have been anxious always to help with drawings and articles for the Bulb Horn, Antique Automobile and other club publications. In this connection, I got to know such good friends as John Leathers, Everett Dickinson, Walter MacIlvain and the equally agreeable staff members of the other club journals. Their dedication may be judged by the scope and quality of our magazines today. Our counterparts in England express their wonderment with "But how do you do it?"

The Saturday Evening Post, circa 1939

The Saturday Evening Post, circa 1939 The Saturday Evening Post, circa 1940

The Saturday Evening Post, circa 1940

Upon the death of George Sessions1941 and through the established friendship of Joe Tracy with the Sessions family Locomobile "Old 16"

came our way

Jerry Helck's recollection of the purchase of the 1908 Locomobile race car:

Using Joe Tracy as intermediary, Dad offered George Session's widow $2,000, a significant sum in those days. There was one other serious bidder, James Melton, the actor and opera singer. Melton swept into Mrs. Session's small house, wearing a floor-length fur coat and placed a partially filled out check on her mantelpiece. He asked her to think about a price and fill it in when she reached a decision, and then call him. Apparently, the thrifty Connecticut housewife was so put off by Melton's Hollywood flamboyance and extravagance that she instead accepted my father's more modest offer.

Regrettably, I was not included in the trip to Bristol (in February 1942) to claim the car; that was my father, Joe Tracy and Ernest’s job. Of course everything took longer than anticipated and while Sessions had mounted lights front and back, they were Model T Ford era, and Tracy couldn’t abide by my father's 30 MPH limit for more than a few minutes. But they did arrive without accident (until Joe grazed the stone wall at the driveway in Boston Corners, bursting a tire).

NOTE: the purchase price was previously reported here as $20,000, not $2,000.

. This was an important moment in life in Boston Corners, and it furthered our association with Old Joe. His visits here were more frequent, and we observed with deep satisfaction the pal-like comraderie shared by 12-year old Jerry and the 65-year old motor veteran. I'm sure the youngster gained much from this companionship.

Tracy came into VMCCA, was made Honorary Member and thoroughly enjoyed the status of rejuvenated celebrity. Consistent with this concern for racing's past, the New York Region organized a series of meets; Simplex Night, Vanderbilt Cup Night, Mercer Night, to which were invited guests who had known fame in days past: DePalma, Robertson, Ralph Mulford, Al Poole, Herman Broesel. Mercer Night brought several surviving executives of the old Trenton marque. All were stunned and unbelieving upon learning the current value of T-head Raceabouts.

1943With the war the ranks dwindled. Water Levino and Ed Bennett appeared when leaves permitted. Hemp Oliver and Austin Clark were far less available. The more elderly standbys, Leo Peters, Joseph Reutershan, Charlie Stich, Bob Bohaty, Sam Baily, Harold Kraft plus the exuberant Ulmann-Gilette team kept the New York Region moving. Jim Melton could be counted on for the Christmas Annual, one of these made memorable by his soul-stirring rendering of "My Boy Bill."

It was around 1942 1942when the Automobile Old Timers was founded, due mainly to the initiative of Frederick Elliott whose entire life had been spent in the regulatory provinces of automobiling. He had been the youthful Secretary of A.A.A. almost at time of its birth. His name is encountered on endless committees supervising trade practices, road improvement, all forms of motor competition. Whether or not A.O.T. was his inspiration, it was his wide acquaintance throughout the industry and his skills in enlisting support from those of influence that built this organization into sufficient membership to stage an annual luncheon attended by 500 or more A.O.T.s from all over the country.

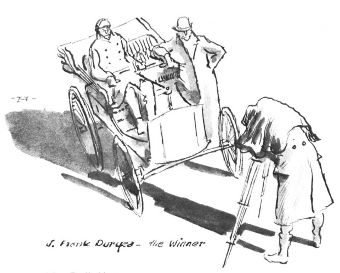

Time Magazine, December 8, 1941.

Time Magazine, December 8, 1941.At these luncheons, usually at the Hotel Roosevelt, citations were awarded to men renowned in the auto world, most of them truly "old timers." Charles Kettering, Julian Chase, Charles B. King, W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr., had been so honored, as would be this writer 24 years later. Consideration of similar recognition had been given Frank Duryea, an eventuality fraught with complexities because of the unsettled claim as to which of the Duryea brothers, Frank or the late Charles E., were to be credited with the building of America's first gas-propelled automobile. The feud had long and not always gently advanced. Among those on the rostrum this day was Frank Duryea. It seems likely that most of the guests were aware of the conflicting claims, but if not, were soon to be. Frank's newphew Jerry visited table after table in a petition drive to have his uncle's citation awarded posthumously to his father. In this crusade Jerry was brushed-off, for the most part good humoredly as he was generally liked and probably admired for his family loyalty.

The meal over with, attention was directed to the awards ceremony. When Frank Duryea was called to receive his, Jerry strode forth, faced the rostrum and heatedly protested this action. The big banquet salon was suddenly shocked into total silence. Frank's thin face paled. The proceedings were held in suspense. The tense situation called for immediate rescue. This was promptly given by arch-diplomat and pioneer automotive promoter Alfred Reeves. He poured on the proverbial oil with such tact that Jerry's retreat was possible without great loss of face as the presentation was made to his uncle Frank. The situation was further relieved by the hasty call for the next recipient.

All present had witnessed a bit of drama, involving human behavioral conduct, reaching an unforgettable split-second climax, and then brought under control by a suave and accomplished trouble shooter.

The Saturday Evening Post, March 27 & September 18, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post, circa 1945 and Army Transportation Journal, August 1945

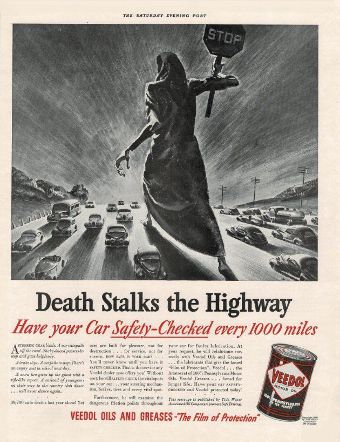

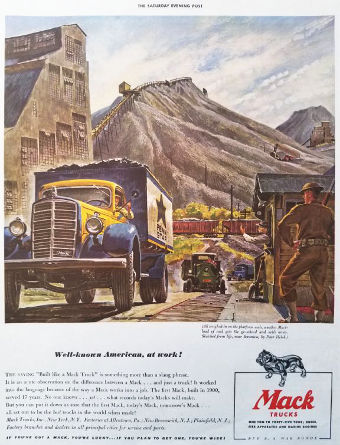

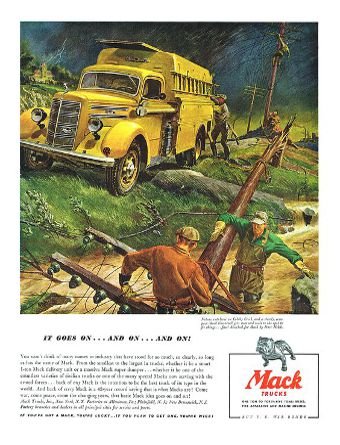

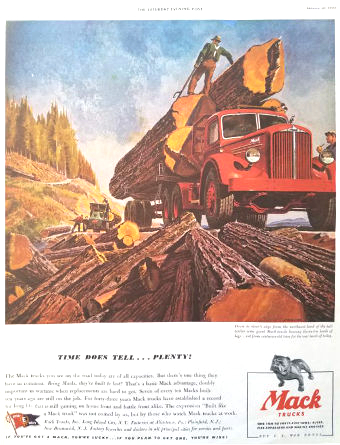

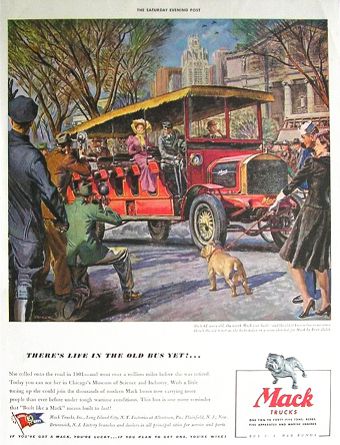

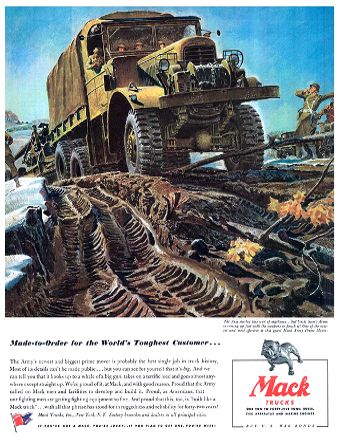

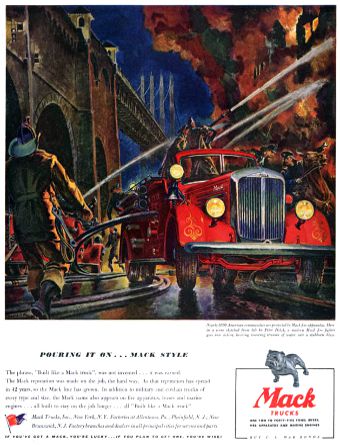

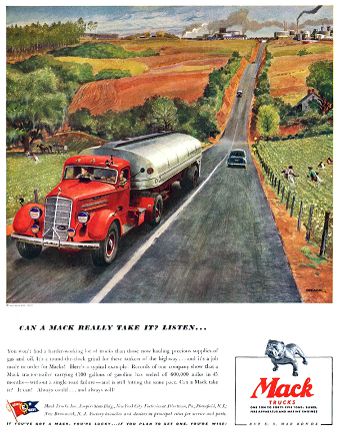

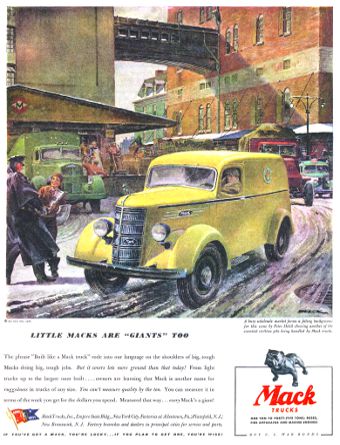

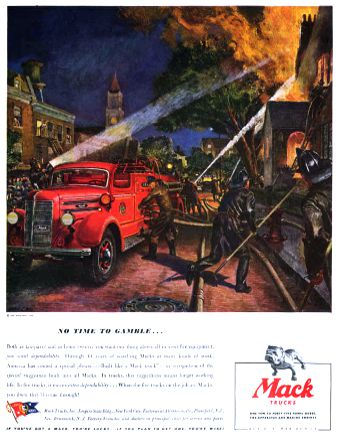

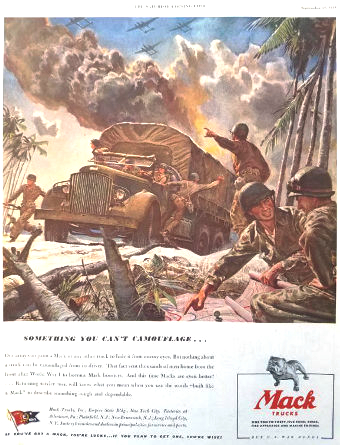

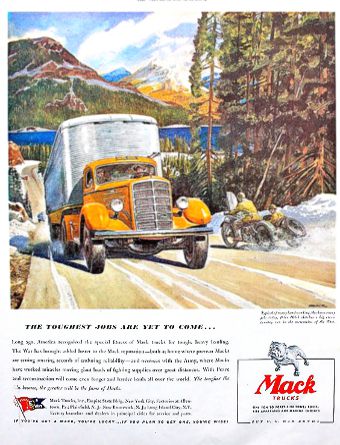

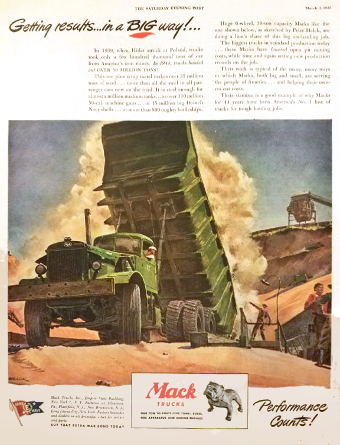

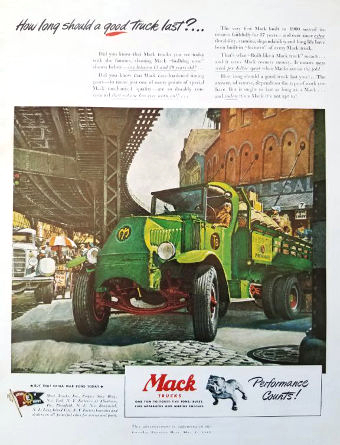

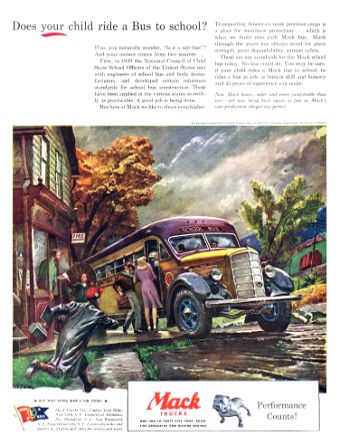

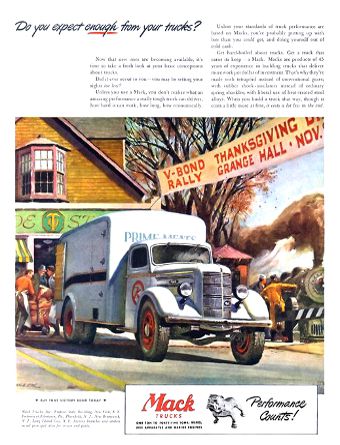

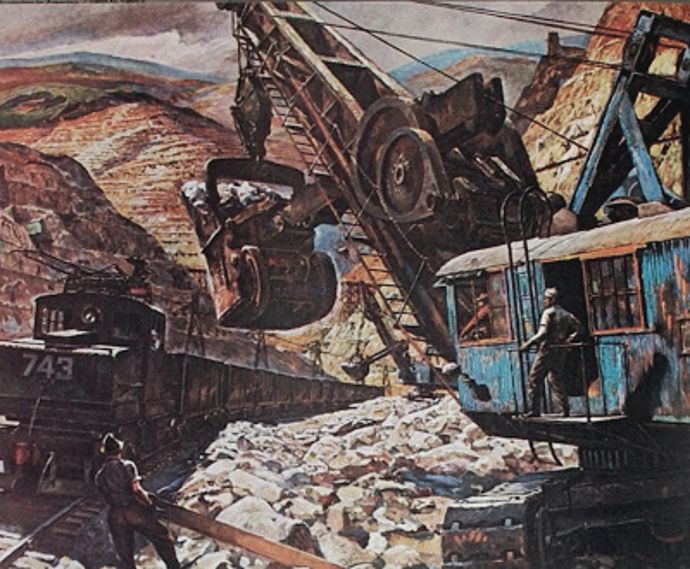

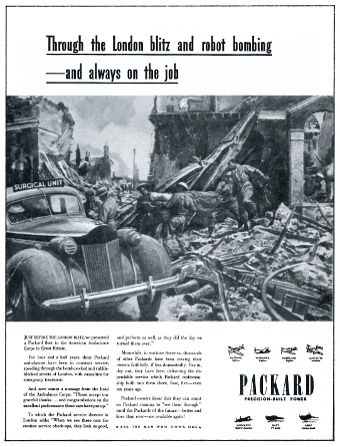

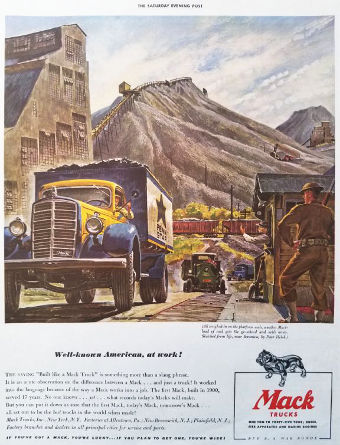

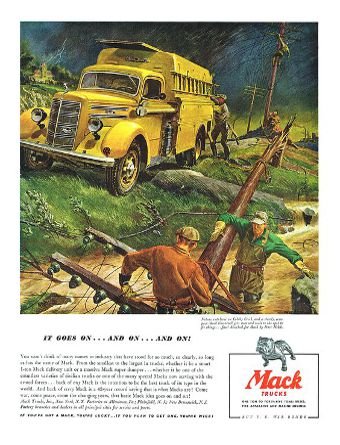

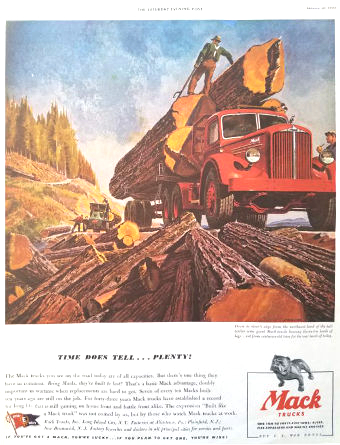

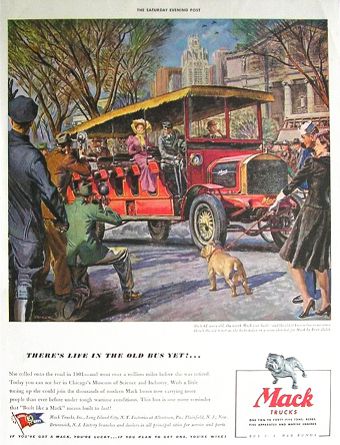

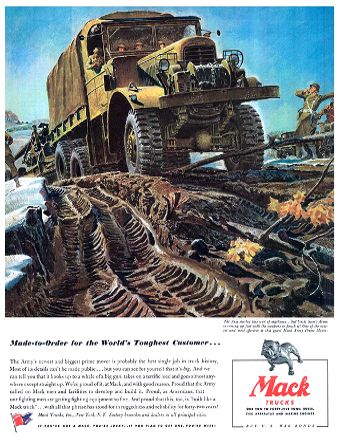

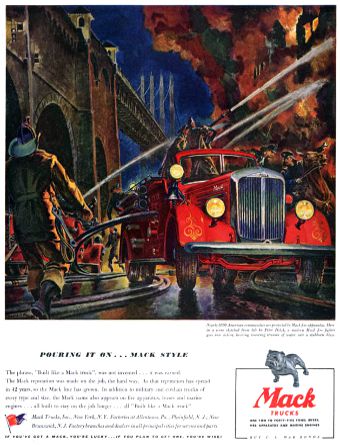

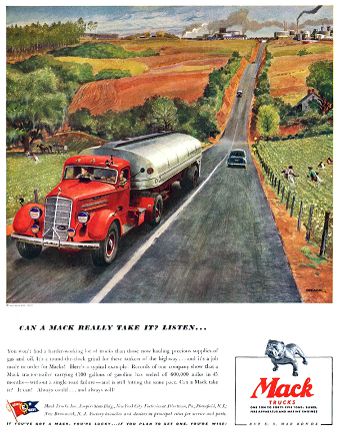

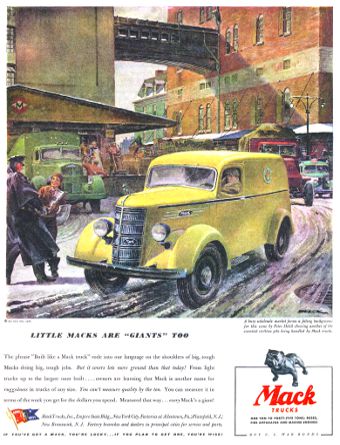

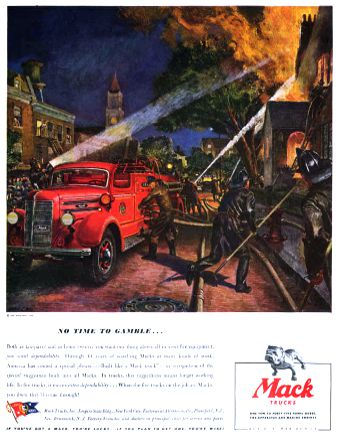

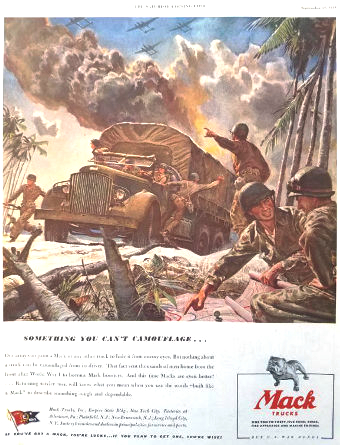

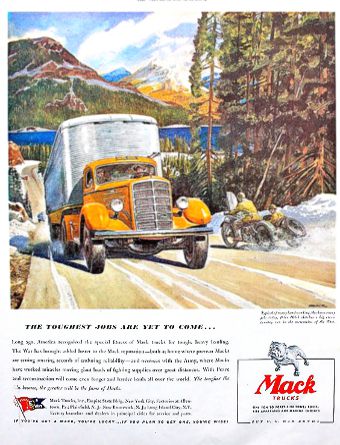

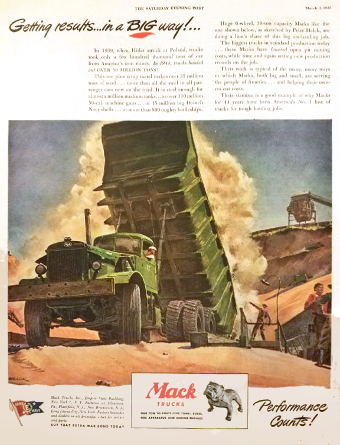

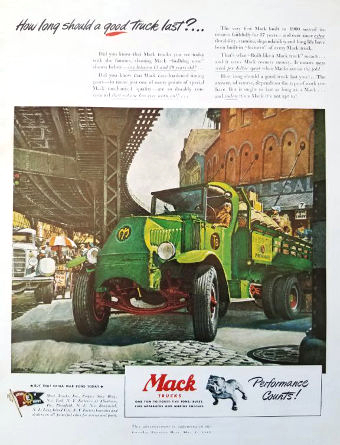

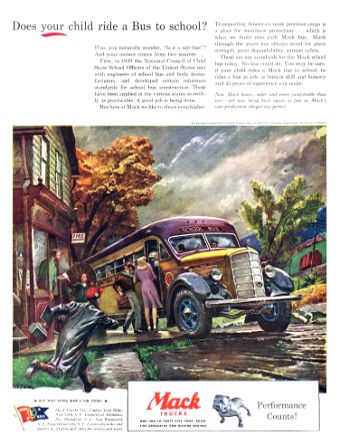

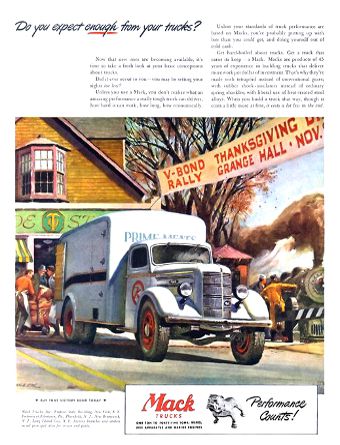

During the early forties, the War years, most of my work was for clients closely involved in the war effort: Mack Trucks, G. E., Timken, railroads, air lines, Republic Steel and other heavy industrials. I was less lucky with work for various Government bureaus. Of many poster designs submitted, only two had been published. Work for the steel corporations was particularly attractive as it necessitated sketching within these thrilling environments, at times a bit hazardous. The year 1944 1944brought a turning point. As a freelance for 29 years, commissions for early motoring and racing subjects had been infrequent. Some of these have been referred to. The rest comprised a few fiction illustrations and a 3-year campaign for Champion Spark Plugs in which racing scenes were incidental to the giant display of the product, the plug.

The Saturday Evening Post, September 12, 1942

The Saturday Evening Post, September 12, 1942 The Saturday Evening Post, October 17, 1942

The Saturday Evening Post, October 17, 1942

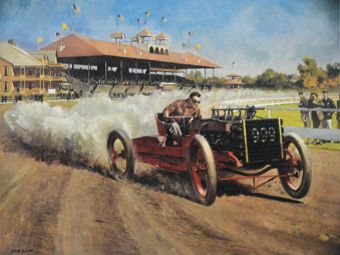

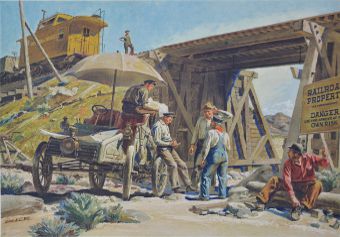

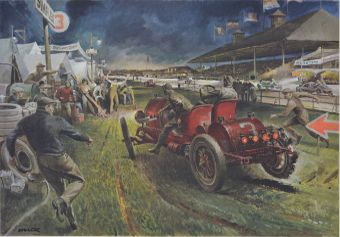

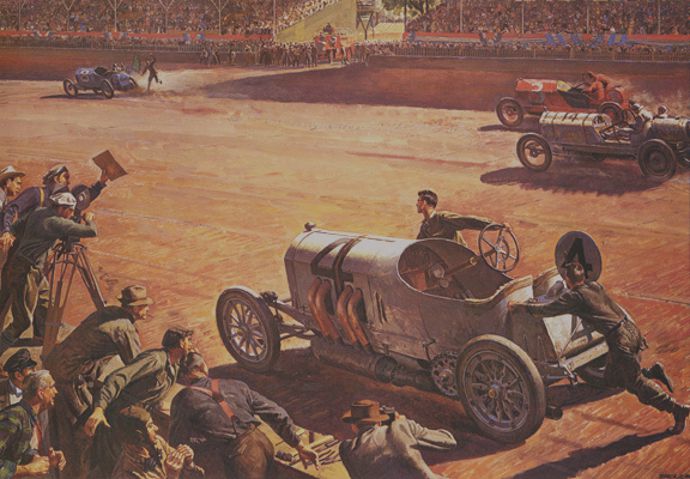

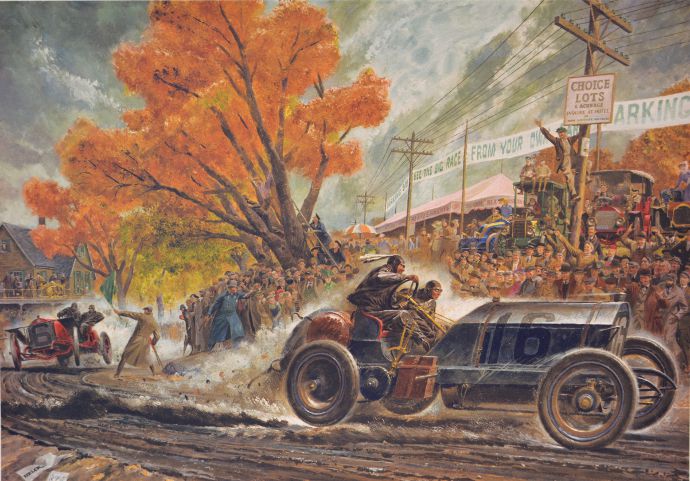

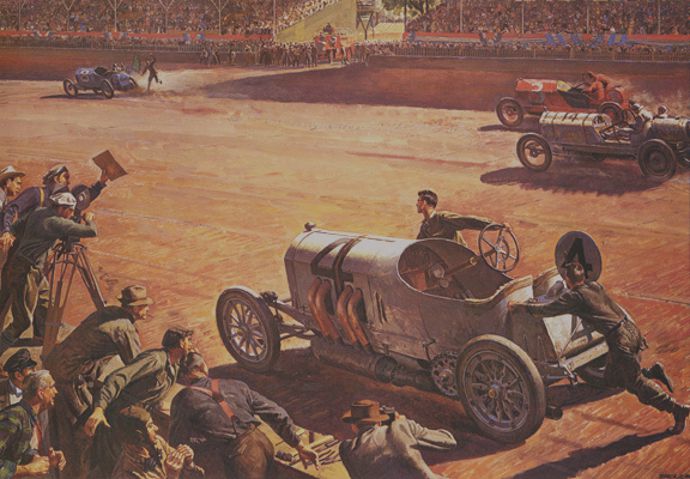

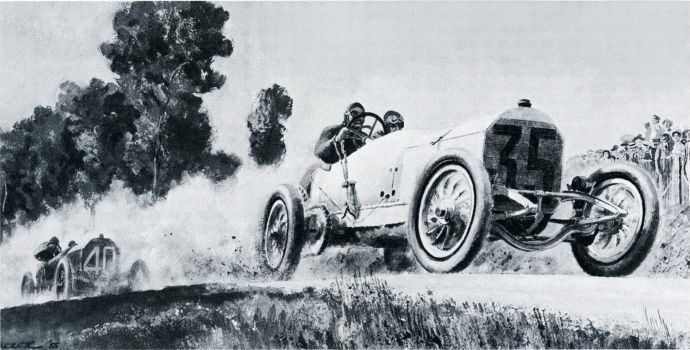

The turning point came when Esquire asked me to contribute to their series, "Great Moments in American Sport." They had me down for Bobby Jones, Babe Ruth or Man of War. I countered with the Vanderbilt Cup. "But that's a Bridge tournament" was the Editor's rejoinder. It took a carefully-done sketch (on speculation) to convince Editor Geis that the first U. S. victory in classic auto racing, Robertson's and the Loco's win in the 1908 Vanderbilt, was indeed a great moment in American Sport.

The Saturday Evening Post, January 30, 1943

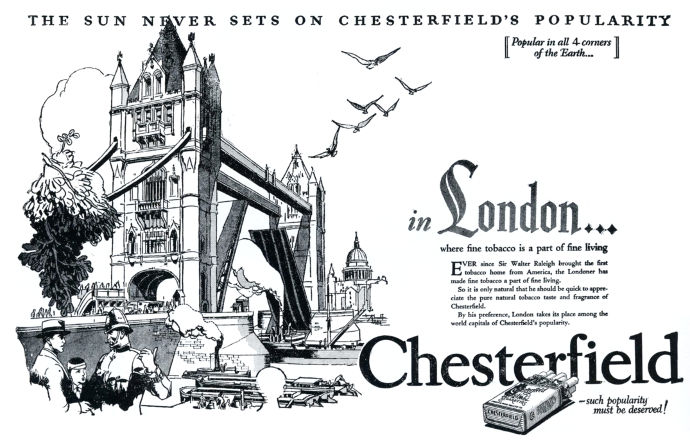

The Saturday Evening Post, January 30, 1943 The Saturday Evening Post, May 1, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post, May 1, 1943

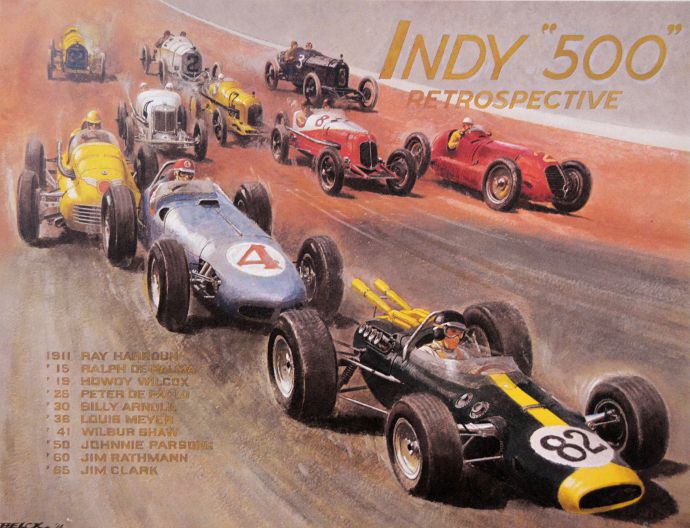

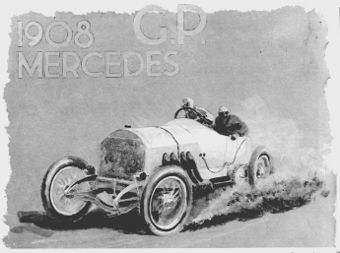

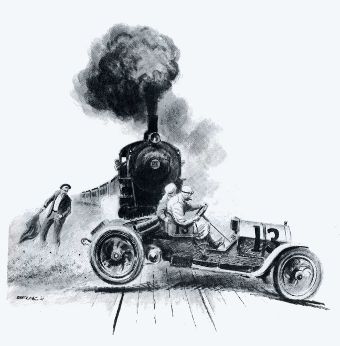

With enthusiastic acceptance of the finished painting, I was immediately prepared to follow through and thus flashed Mr. Geis with a sketch, hopefully executed, of another "Great Moment", the 1912 Indy "500" where Depalma's Mercedes had led from the 10th to the 496th mile, faltered, then limped to a standstill. Driver and mechanic pushed the stricken car for a lap in a desperate but fruitless effort to win. The sketch was okayed and was the basis for six more subjects all close to the heart, and for which Founding VMCCA Member John Leathers wrote stirring commentaries. The set of eight were ably promoted in the magazine, by exhibitions of the originals in major cities (two of the paintings disappeared along the wayl) and by a limited edition folio, copies of which were presented to important people in the auto industry. This fortuitous gesture was, according to Esquire, largely responsible for Detroit's Golden Jubilee in 1946. Plans for this celebration were at the point of withering because of general apathy. However, a committee member produced this folio, showed it around with the resultant verdict "By Golly, there's still romance in the Automobile!"

The Saturday Evening Post, November 28, 1942

The Saturday Evening Post, November 28, 1942 The Saturday Evening Post, January 23, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post, January 23, 1943

Negotiations with Esquire had been unique and educational. At the outset I was assured of receiving their "top price." Although unknowing of Esquire's rates, the figure offered was well below that of the general magazine level. Upon approval of the preliminary sketch I was again assured of the "top price" now at a 50% increase above the first quotation. Laughingly I suggested resuming negotiations a bit later when this climbing scale could possibly escalate to an honest "top price."

The Saturday Evening Post, July 24, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post, July 24, 1943 The Saturday Evening Post, October 16, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post, October 16, 1943

Twenty years later fan mail still arrives proving the ever-growing interest in the vintage periods. Accordingly, about ten years ago Austin Clark, with Esquire's blessing, republished the set in deluxe style.

The Saturday Evening Post, January 15, 1944

The Saturday Evening Post, January 15, 1944 The Saturday Evening Post, May 27, 1944

The Saturday Evening Post, May 27, 1944

Despite the War's gas restrictions, meets were contrived, one for China Relief (consider that one in view of subsequent world affairs!) at Fairfield, Connecticut. Melton zeal for the resounding success of this benefit stirred me into donating a half-dozen paintings and drawings for auction, the returns from which were disappointing. Later the enterprising Ulmann-Gillette leadership slated a two-day meet at the Helck residence at Boston Corners. About 30 cars appeared, arousing much local curiosity as to the means by which these gas-burners got around rationing. We were lucky in having Depalma, Tracy and Poole give the affair a note of distinction, further embellished by the presence of Herb Fales' guest, Geoffrey Smith, long time Editor of The Autocar of London. A deeply sentimental note that day was an exhibition run, at a snappy pace, by the Loco, Tracy driving, Poole at his side, quite as I had seen them 30 years before in the Vanderbilt.

The Saturday Evening Post, September 23, 1944

The Saturday Evening Post, September 23, 1944 The Saturday Evening Post, December 16, 1944

The Saturday Evening Post, December 16, 1944

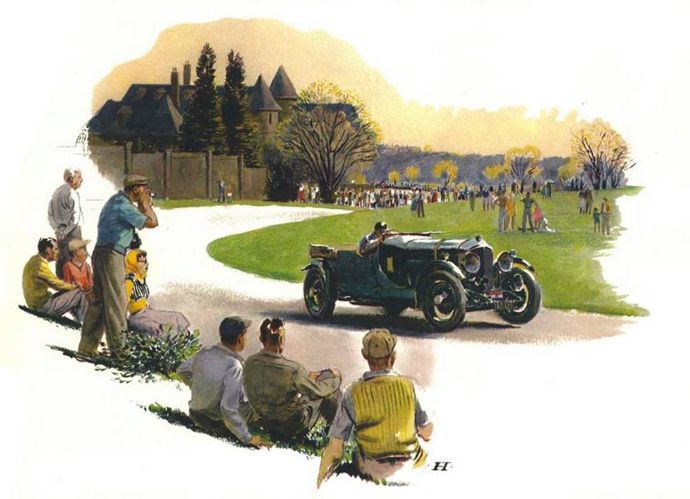

The War's end allowed more ambitious club activities, and in 1946,1946 thanks to Jim Melton, his wide influence and a handful of go-workers, the first Glidden Tour Revival was presented. Some 150 cars of wide range of HP and mph participated. As Tracy, Poole and Robertson were unavailable to co-drive the Loco, I contacted Frank Lescault, a distinguished driver of Matheson, Palmer-Singer and Simplex cars in track and road racing circa 1908. A word about Lescault seems fitting. As Sheriff, he was the only Democrat and Roman Catholic ever elected to office in Schoharie County, New York, and a most-loved character in his community. Less commendable was his road deportment on the Glidden, a jovial disregard for all the official restraints. Otherwise he was a delightful companion with a wealth of anecdotes enthralling to all listeners. Good old Frank, now gone, but affectionately remembered for his geniality and all-around goodness. Knowing these virtues, it was with shock and disbelief that I heard the following from one of his friends and racing contemporaries. "We were a fast-living crowd, wine and women, a don't-give-a-care sort of existence. I'm afraid we were a pretty rough bunch." A pause, and then, "Not as bad as Frank Lescault, you understand, not THAT bad!"

The Saturday Evening Post, March 3, 1945

The Saturday Evening Post, March 3, 1945 The Saturday Evening Post, May 5, 1945

The Saturday Evening Post, May 5, 1945

Our Glidden "team" included Jerry and that fabulous chap, Charles Lytle, race historian whose photo collection must be the most comprehensive in existence. Charles assisted in driving our "service" station wagon but his quest for photos frequently carried him off the Tour route. Because the Tour had been excellently publicized, in towns along the way were curious oldsters whose lives had been spent in connection with cars. In Rochester we met Billy Knipper, veteran of road and track. Then there was the sad-faced little character in Buffalo, W. E. Vibert (better known as Curley) who had been Spooner and Wells' ace photographer and personally responsible for hundreds of camera shots of the original Glidden Tours and the major road racing events in the East. Poor Curley, his collection of plates and prints had perished in a fire. In dejection he rid himself of his studio, cameras and all equipment. Mourning for these losses had become occupational.

The Saturday Evening Post, September 8, 1945

The Saturday Evening Post, September 8, 1945 The Saturday Evening Post, November 2, 1945

The Saturday Evening Post, November 2, 1945

On a couple of occasions when leaving the Loco unattended in roped-off areas allegedly being patrolled, we returned to find seventyish-aged strangers sitting at the controls with focused cameras clicking merrily. One intruder countered our objections with who's got a better right? Wasn't I in the Loco pits that day when George won the cup?" All along the line we found gentlemen of all ages who claimed to have been factory hands in Bridgeport.

Esquire, Climb to the Clouds

Esquire, Climb to the CloudsSpeaking of the aged, there was a notable one, most fittingly, on the Tour, Colonel Augustus Post, writer, artist, musician, balloonist, headline hunter and White Steamer pilot on the first original Glidden!

We ran again in the 1947 1947Glidden, a tour through New England, with the late Frank Lescault again as co-driver. I recall the dash through pouring rain on the way to Portsmouth, the pelting drops stinging hands and face, a thoroughly enjoyable sensation, but one Frank chose to avoid. He followed our spray in the station wagon. Jerry and I were thoroughly soaked and chilled, but the cheery blaze in the Wentworth Hotel's fireplace, a change of clothes and the congeniality of such jovial Gliddenites as Les Taylor, George Crittenden and Bob Bohaty restored us to cozy well-being. Another recollection is the sight of Charles and Marion Bishop struggling to the summit of Mt. Washington in their gentle-powered Delaunay, giving this elegant lightweight undeserved punishment. The Chaynes' tour car was a 1910 Buick in such pristine condition as to have impressed everybody. Then one day Charlie appeared from nowhere at the wheel of the gargantuan Bugatti Royale! Seeing it WAS believing, I suppose. Beside this mighty apparition the hundred-odd tour cars (and there were some exotic numbers, be assured) paled into insignificance.

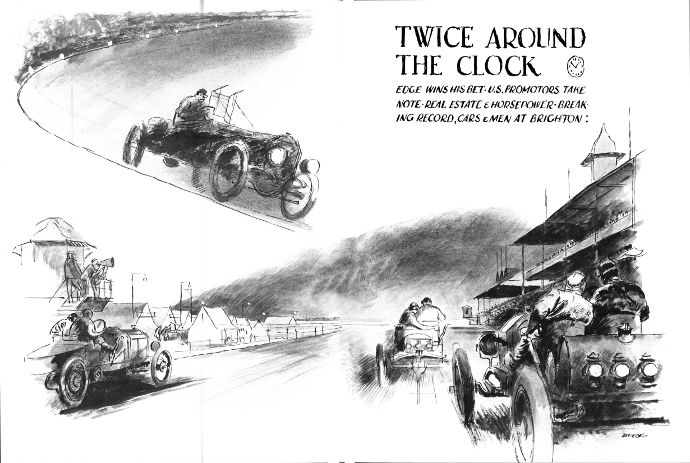

Esquire, Transcontinental Interlude

Esquire, Transcontinental Interlude Esquire, The Brighton 24 Hour

Esquire, The Brighton 24 Hour

The Tours have continued annually ever since, attaining popularity and elegance perhaps unforeseen even by poor Jim Melton.

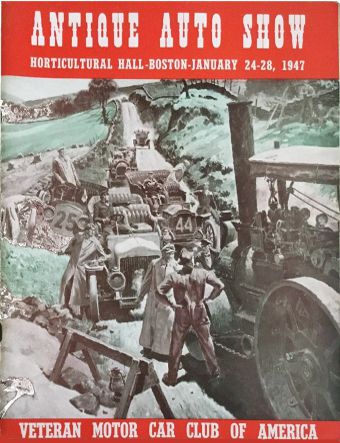

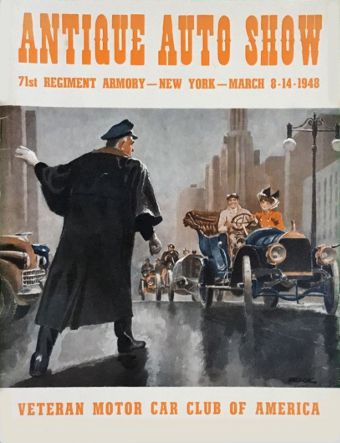

An outstanding Club achievement was New York's first Antique Auto Show in March 1948 1948at the 71st Regiment Armory. The three major clubs, VMCCA, AACA, HCCA and the young SCCA pooled their administrative and publicity talents and displayed about 80 cars (from 1896 to 1922) for seven days to an audience of 30,000 curious New Yorkers, with generous recognition in the New York dailies and the news weeklies. Nothing before or since so alerted a jaded city to the historical significance of the automobile. Credit for this success is due Show Manager, the late and popular Jerry Duryea, and VMCCA officers Austin Clark, Alec Ulmann, Henry Finn and the numerous committees served by most of those prominent in inter-club affairs at that time.

Esquire, Robertson Comes Through

Esquire, Robertson Comes ThroughFor us personally the Show was momentous. "Old 16" was voted the Grand Prize and its presence brought together the four who had served as its crews in 1906 and 1908, Tracy and Poole, Robertson and Ethridge as well as other racing notables of that period. Particularly welcome at our stand were Larry and Eleanor Riker, most fittingly as Larry's father, A. L. Riker, was Locomobile's Chief Engineer and de- signer of "Old 16." Gift-bearing sentimentalists brought photos, armbands, signal flags, badges, all cherished mementos from the Long Island Cup Races. Car-minded Gary Cooper fiddled with the Loco's controls while TV technicians did their stuff. 1'11 always remember the kindness of hotel owner Jack Stack (deceased) in giving my mother a tour of the show aboard his lovely curved-dash Olds. Some of the outstanding exhibits, alas, have gone West, literally. The New York-Paris winning Thomas Flyer, bought at the Show by Austin Clark from Paul DuPont, is now splendidly restored in the Harrah Collection as is also Mel Brindle's elegant boat-bodied Crane Simplex. I believe the ex-Cameron Peck 1913 Peugeot, second placer at Indy, 1914 is in Briggs Cunningham's Museum in California. All overtures notwithstanding, the 1909 shaft-drive Mercedes Tourer stil I remains an Eastern property, Charie Stitch's.

It may have been in the thirties that the thought of doing a book was given consideration. At that time the American Lithographic Co. exhibited a batch of my racing sketches. The hint of a book may have come from Ralph Stein who saw this little exhibition and stated that it had been a factor in creating his interest in early cars. But it was not until 1947 after the Esquire set had indicated a potential audience, that the book was projected sufficiently to submit to publishers.

Esquire, Gangway for Barney Oldfield

Esquire, Gangway for Barney OldfieldFellow artist and friend Bill Schaldach had become Editor of Countryman's Press, producers of fine books on hunting, fishing, outdoor life generally and a subsidiary of Barnes Publishing. Just as things looked promising some publishing misadventure scuttled the subsidiary and my friend's job as well. Again prospects loomed favorable at McGraw-Hill until that firm decided on doing it as a $5 item, on which scale the artwork would be drastically limited. At Macmillan the script and dummies were left for consideration. In time these were returned in the original wrappings which appeared never to have been opened.

Author friends insisted that my cause was futile without the services of an agent. But in years of freelancing in my own profession without this aid, I felt no need to do anything about it. Anyway, there was no rush. Every reading of the script disclosed need for improvement, and, just as often, new thoughts on format and illustrations were considered and executed. This rehashing, tucked in between assignments, was to go on for years.

Esquire, The Glidden Tour of 1907

Esquire, The Glidden Tour of 1907 Esquire, New York to Paris, 1908

Esquire, New York to Paris, 1908

Quite apart from drawing and painting early automobiles have been experiences with fellow addicts of an acquisitive nature. One such, a kindly old chap who gave still older inmates of nursing homes leisurely rides through the countryside, indicated a passionate wish to own my 1926 American Rolls, a monumental sedan in reasonably good condition. He had set aside a small sum, his Hobby Fund, which, together with two mechanically-minded nephews who would restore the car, was offered as a basis of exchange. After 15 years of resisting his gentle but firm approach the Rolls became his treasure. Within five months it was being advertised as a rare bargain at approximately five times the figure at which he bought it!

There was also the Cole Roadster with a distinct racy flair. An engaging young man by the name of Cole felt strongly that the association of names could be far more meaningful if he possessed this car. There was the sacred pledge that once in his ownership the roadster would be fully restored by himself, and take its place as a beloved family member for untold Cole generations. Unlike the Rolls enthusiast, this applicant was not toting octogenarians on motoring tours, nor did he mention "hobby funds" but he exuded sincerity. I liked him and he got the Cole for what I had given for it, about $150. 1 saw that car again 10 years later, fully restored, not by Cole, in Tony Koveleski's fine little museum in Scranton!

Esquire, De Palma Pushes His Mercedes Home

Esquire, De Palma Pushes His Mercedes HomeAll this recalls an earlier period, the depression years. That they hit people in high places was evidenced by the classic machinery languishing in used car lots, at filling stations, awaiting offers. One such was a magnificent 1929 Pierce-Arrow doublecowl phaeton displaying a sign, "For Sale $35." There was the J-Duesenberg for $100. And the 1907 American Mercedes for which the owner paid a small fee to have it removed from his estate!

Future depressions are not apt to afford another transaction as per the following one effected in this vicinity in the somber thirties. We'll call one of the principals a playboy with a hide-out in the Berkshire Hills. The other was a baker, whose wife decided that unpaid bills of $100 for bread and rolls had reached the limits of expanding debt. Wishing to preserve domestic peace, the baker confronted the delinquent with a demand for settlement. The playboy had no such cash. Was there anything in the house that might compensate? There was not. How about a car? There were several in the garage. The baker, pointing to his sedan, replied, "I gotta car," and made his frustrated departure.

The baker's wife was resolute and uncompromising, so husband tried again. Soon convinced that coin of the realm was not forthcoming and with no other alternative in prospect, he became the grumbling owner of a 1912 Locke-bodied Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost! Domestic harmony restored only after slow enlightenment proved this acquisition to be meaningful. The baker and wife have long since been ardent addicts and prize-winning participants.

With my obliging cousin's gift of the motor journals back in 1905 began my accumulations of all such. Through purchases, trades and presents, by having as friends such mutually-minded devotees as Bob Cochrane, Charles Bishop, Josef Reutershan, Charles Lytle, Leo Peters, Austin Clark, Bob Doty and that unforgettable accumulator of Americana generally, the late Alex Telatco, my collection, though restricted to the 1895-1925 period, is considerable. I had hopes of adding to it in a big way when the library of the venerable Automobile Club of America -- another sad victim of the depression -- was advertised for sale at auction. These hopes rocketed sky-high when a mere handful of interested persons appeared to inspect the several thousand bound volumes, the framed posters and photos. Then suddenly the auction was called off ! My attorney made inquiries. These disclosed that the Bendix Corporation had in a private and seemingly irregular deal acquired this voluminous treasure for a trifling $500!

As for the Bendix bargain, it lay forgotten for some years. Fortunately, before neglect reduced it to a mouldy mass it was rescued and presented to the Public Library.

The bulk of this was shipped to South Bend and dumped not too reverently on a cement basement floor. However, several hundred volumes escaped this fate. Quite by chance I discovered about 300 of these in a small store on Canal Street whose main stock consisted of an indiscriminate range of merchandise and assorted junk. I bought as many as I could afford at 50 cents per. Among these was one of those rare lucky finds that bring on Collectors' Palpitation, a huge leather-bound scrapbook which had been prepared for the A.C.A. This contained full news coverage of the 1905 Vanderbilt plus sixty-five 8 x 10 Spooner & Wells photos of that great race. This bargain compares favorably with that of the Connecticut baker's Rolls-Royce.

In 1948 1948that remarkably successful illustrator, AIbert Dorne, created the home study institution known as the Famous Artists School. It was flattering to be among the dozen chosen to be founding faculty members. Dorne and Fred Ludekens prepared the Basic Course, a 24 lesson textbook, intelligently organized and beautifully printed, which remains the foundation of the enterprise. For the Advanced Course the twelve of us wrote our own books of instruction, each designed to attract students believed to have personal interest in our particular and singular working methods. The best part of a year was given to writing and illustrating my course.

The published courses won wide acclaim for their layout and typography quite aside from their merit as means of instruction. Enrollments in the Basic Course were immediately forthcoming on a level with Dorne's anticipation. However that brilliant fellow's judgment as to similar appeal for the Advanced Courses had been overly optimistic. Only Norman Rockwell and Al Parker had great numbers of starry-eyed student admirers. The egos of the rest of us were somewhat deflated by the modest enrollments for our Courses.

For four or five years I corrected the work of my students. As this meant graphically-demonstrated means by which their works could be improved plus typed analysis and criticism, teaching via correspondence was time-consuming, on occasion six or seven hours on a single assignment, but also very enjoyable. In time the Advanced Course was merged with the Basic and the later Painting Course.

At the time of the school's founding, teaching art by mail was viewed by many as suspect, and with cause. One nationally known school had not revised its course for 27 years. When our Basic Course Lesson No. 16 brought drop-outs and other evidence of fading student interest, Dorne concluded that this lesson, not the students, was the cause. No. 16 and others later were reorganized for improved clarity. Our humble beginning in a little cottage on Boston Post Road has become an institution having about 115,000 students in art, writing and photography.

The School's instruction fostered the traditional art fundamentals: sound drawing, perspective, representations as offered by nature, most of which is scorned by the avant-garde. My personal work for exhibitions continued traditional and was thus recognized by one of the few remaining art bodies unaffected by the radical movements, the National Academy, to which I was elected in 1950. At the present there is slowly emerging a return to recognizable subject matter in painting. The astounding success of realist and traditionalist Andrew Wyeth may be viewed as significant.

General Electric calendar, 1947.

General Electric calendar, 1947.The following year 1951provided a delightful return to Europe, a three month tour in a beat-up Austin station wagon with convivial Charles Lytle and my son Jerry. In his third year at R.P.I., Jerry was given last minute permission by his draft board for this period. That this was to be a strictly non-art pilgrimage was evident upon arrival at LeHavre where Lytle awaited us with a precise itinerary and the shabby conveyance he had engaged to expedite this program. In short, we would attend the major races, become acquainted with their personnel, investigate historic circuits and personally meet the veterans who had raced over them.

As to the latter, during the war years Charles had been generous with food and goody packages. As an avid collector of racing photos it was possible to believe he was not seeking forms of reciprocity from these elderly gift recipients.

Off we rattled for LeMans and the 24-hour Annual. At the Auto Club de la Ouest, amid the frantic onslaught of press representatives clamoring for credentials, our Charles demonstrated those rare diplomatic skills which recognize no frustration. He returned from this linguistic melee with pit and general passes for three! We toured the famous circuit, alive with preparations, police, soldiers, building activities, tents, parking spaces and always the stout barricades all around the course. Each of us drove a lap, noting the characteristic landmarks: Virages, Hippodrome Cafe, the Esses, White House and the long climb to the colorful tribunes. As rain fell we parked at the pits to partake of the life-behind-the scenes. We met Henry Lallement, Dunlop racing chief, and that well known company asset, "Dunlop Mac". Many familiar faces were present, Briggs Cunningham, Alfred Momo, George Rand, John Fitch, George and Mrs. Weaver, George Huntoon, Tom Cole, Sam and Mabel Baily, Bill Spear.

General Electric calendar, 1948.

General Electric calendar, 1948.Night practice was interesting viewed from the Cunningham pit. Rain fell heavily, dropping from the helmet of Weaver as he paused during his 300-mile jaunt in easing-in a new bench-tested engine. Opposite the pits stood the thousands without cover in the downpour. The biting roar of fast cars, the floodlighting, the wet, the jostling of intruders in the pit, Kay Petre and gals in slacks, all provided a colorful spectacle during the night hours.

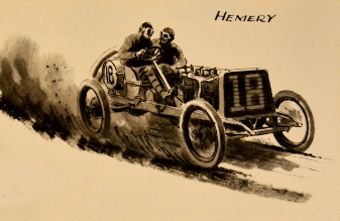

The day of the race we visited Cunningham's garage and saw his trio of contenders in last-minute preparation. In fact the rear ends were out of all three and the engine of one about to be remounted. This with the race within a few hours of starting here we met that booster of New York VMCCA projects, Alec Ulmann, his wife Mary and "little Eddie". Conforming to Lytle planning, we visited the home of the late Victor Hemery, French racing ace who had forsaken Darracq to drive for arch-foes Mercedes and Benz. The year before Hemp Oliver had a cordial meeting with the old champ a few months before his suicide.

The race, for all its attending glamour, seemed less interesting than the preliminaries just preceding its start. Charles continued his pursuit of people "we should know," while Jerry, with or without consent, photographed such notables as Louis Chiron, W. F. Bradley, Luigi Chinetti, Louis Rosier, Laurence Pomeroy. Most impressive personage was the official starter, the venerable Charles Faroux, in magnificent plus-fours and a wide-brimmed Borsalini with cavalier flair.

Leaving LeMans en route to Chartres we glimpsed a super railcar skimming over the shining rails at lightning speed. Was this one of Ettore Bugatti's much publicized creations we wondered? In Chartres we parked in the plaza of its grand Cathedral, finding its unsymmetrical facade quite like both of its impressions painted by distinctly-opposed "modern" painters Soutine and Utrillo. The interior seemed to cast a deep spell of reverence and wonderment within Jerry. He was disinclined to explore the sacred premises, viewing such curiosity as intrusion, I suspected. While respecting this reserve I explained that for centuries such edifices had received visitors from all over, that scuffling feet had resounded through the ages, that each and every "intrusion" became factors in sustaining the prestige of the entire church hierarchy.

Regarding famous old racing sites, we hunted up Dourdon and Arpagon, straightaway strips over which sprint records had been set by the early speed kings. So we hurtled our creaking van over The Dourdon Kilomtre, reliving the flying dash of the electric juggernaut La Jamais Content, only to find later that Jenatzy's 1899 records had been made at Acheres! Another goof followed shortly on the way to Arpagon. With Lytle manhandling our crate, we struck a dog with resultant sequence involving local police, a boy's unhappy tears and our voluntary appeasement of 2000 francs. Arpagon seemed hardly worth the life of a pet or the anguish of its young owner.

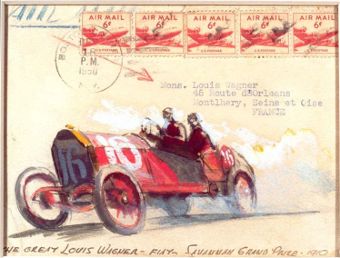

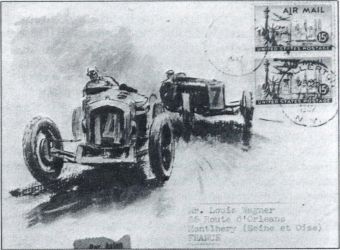

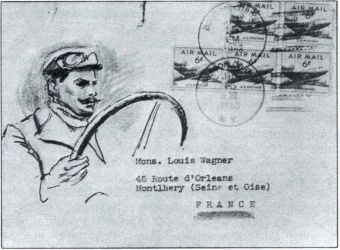

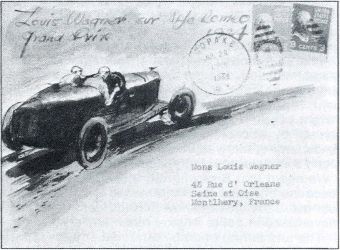

Louis Wagner winning the 1908 Savannah Grand Prize, the painting presented to Wagner by the artist in 1948.